If Snap wanted to juice user growth, they could.

John Necef, Head of Growth at The Hustle, illustrated potential ways for Snap to continue to grow.

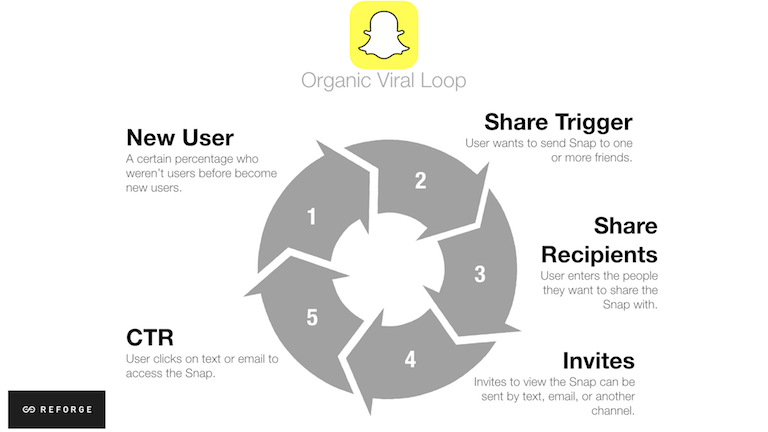

To summarize, he recommends accelerating what we at Reforge call Snapchat’s organic viral loop by improving the loop at different points:

- Make “Quick Add” friends more prominent. Increasing the frequency of the trigger

-

Improve the channel. By adding more guest invite channels

-

Contextual invites. Which would improve the CTR

While I agree in theory that these changes would kickstart user growth, I want to point out that it’s likely that Snap has a good reason to NOT blatantly push the “Quick Add” feature or to constantly ask for access to contacts.

Facebook’s “People You May Know” feature was incredible for user growth, but it also had a negative side effect. By adding more users, its content became more public. The more public it became, the less younger users engaged with the platform, if at all. (No one wanted to share pics from Friday night, knowing moms, dads, and teachers might see it on Monday.)

That’s why these decisions don’t feel like low hanging fruit, but rather a deliberate strategy to make Snapchat feel like a personal, authentic platform where users can be themselves, unlike on Facebook (where younger audiences rarely post) and Instagram (where they create fake accounts — “Finstas” — so they can be authentic again).

I don’t want to hypothesize about how Snapchat’s new UX might add user growth without alienating its core user base, because I don’t know. Instead, let’s take a broader look at why I believe Snapchat can still beat Facebook/Instagram as the communication platform for the teenage demographic, regardless of how much market share Kylie Jenner wipes out with a single tweet.[note]Bloomberg Technology – Feb 22, 2018 | In One Tweet, Kylie Jenner Wiped Out $1.3 Billion of Snap’s Market Value – https://goo.gl/gX2LXH[/note]

To do that, first, let’s get an understanding of where Snap is today.

A brief look at Snapchat’s landscape

The Daily Beast leaked a ton of Snapchat’s user data. First, let’s look at the good:

Chat

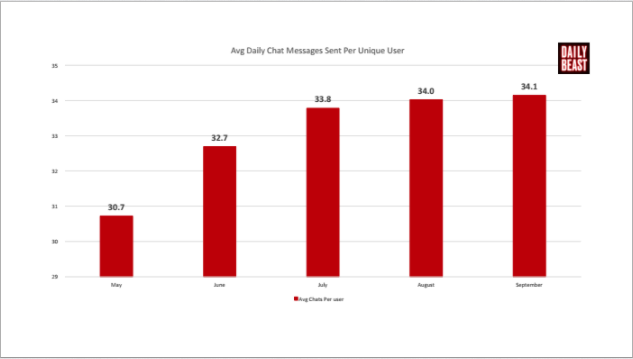

In August 2017, users sent an average of 34 chat messages per day.

Time

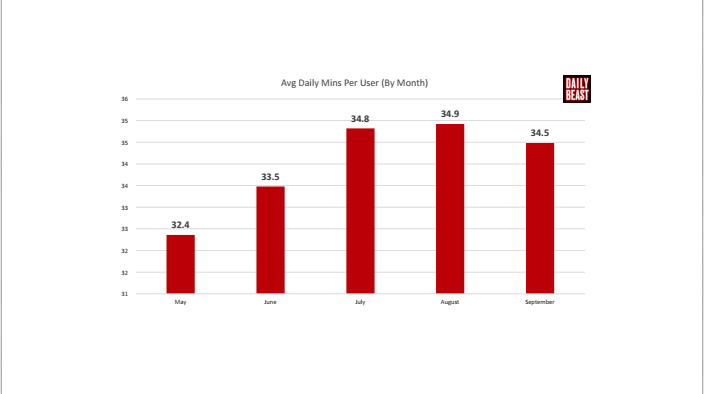

They spent an average of 34.9 minutes on the app per day.

Snaps

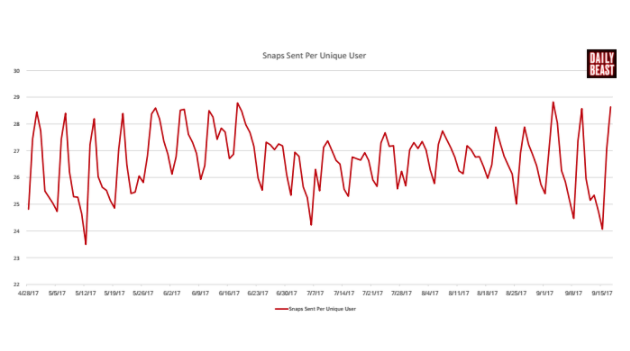

Users also sent an incredible number of snaps — about 27 per unique user.

Snap has even seen some user growth after a prolonged stagnation. During the Q4 2017 earnings call, CEO Evan Spiegel said that “content consumption and time spent in the redesigned application are disproportionately higher for users over the age of 35,” signaling progress in older demographics, Snapchat’s notorious Achilles heel.

Now, the bad: usage of other Snapchat products continues to trend down or sideways.

Maps

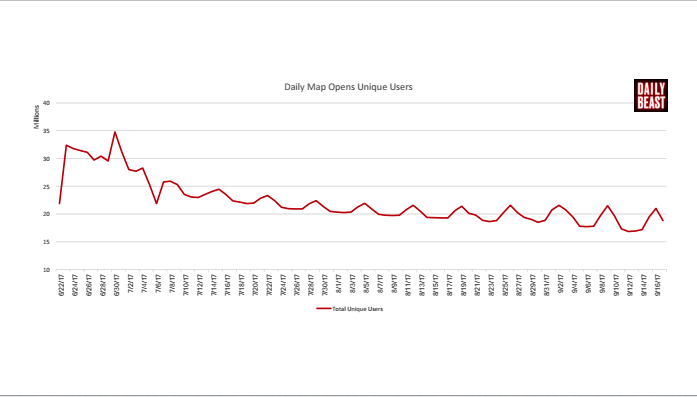

In the month of September, an average of only 19 million users checked Snap Maps daily, just 11 percent of the app’s total daily user base.

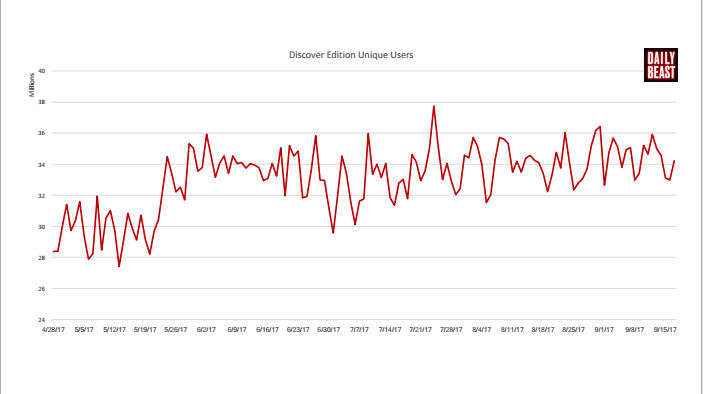

Discover

Discover is trending sideways, with peak consumption on July 24, 2017, at 38 million daily unique users, around 21 percent of the broader user base.

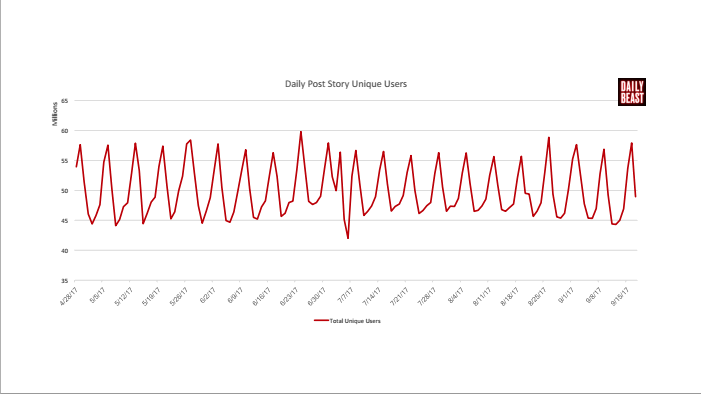

Stories

Facebook, Instagram, and Whatsapp (all Facebook Products) launched their own Stories product, which essentially nerfed Snapchat’s Story.

Not helping matters is the fact that it’s against Snapchat etiquette to take a direct Snap and use it in a Story. In other words, Snaps are private while Stories are for the world. That’s why — as we see in the data — an increase in Snaps doesn’t necessarily have strong correlation with growth of Stories.

Perhaps it is unfair. But it doesn’t really matter.

Copying is just business

As Brian Balfour put it, “copying what’s working is a winning strategy, and one we’d probably all go after if we were in the driver’s seat at one of these companies.”

Facebook knows this just as well as Snap, having been on the “victim” side of copying nearly a decade ago. In October 2005, a German company called studiVZ launched at German universities. It borrowed Facebook’s design, with one tweak — blue elements became red. Otherwise, it was an exact replica. By January 2007, it had 1.5 million users.

Meanwhile, in China, another social network launched called Xiaonei, growing to millions of users. Xiaonei directly copied Facebook’s software code, and even included “A Mark Zuckerberg Production” at the bottom of each page. [note]The Facebook Effect: The Inside Story of the Company That Is Connecting the World by David Kirkpatrick | pg.171[/note]

Facebook is also well-versed in playing the underdog role in the David versus Goliath narrative. It was only six years ago that Google announced that their new Google Plus product had 400 million users and 100 million active users.

When Google launched their competing social network, Facebook gathered all its employees in a town hall meeting and declared war. The contest for users, Zuckerberg told employees, would now be direct and zero-sum.

“You know, one of my favorite Roman orators ended every speech with the phrase: Carthago delenda est. ‘Carthage must be destroyed.’ For some reason I think of that now,” Zuckerberg said.

“Carthago delenda est” became Facebook’s rally cry. Posters went up on the Facebook campus. Facebook employees were encouraged to come to work seven days a week, and families were allowed to visit on weekends and eat in the cafes.

Facebook went to war and eventually emerged victorious.[note]Chaos Monkeys: Obscene Fortune and Random Failure in Silicon Valley by Antonio Garcia Martinez | pg. 288[/note] Google Plus was not Facebook. And although Facebook can certainly copy Snapchat Stories with a high degree of success with Instagram Stories, it’s still not Snapchat. Facebook can do Bonfire, but it’s not Houseparty. They are different tools, to be used in different contexts. Cracking the context code is not as simple as replicating actual code, and fortunately for Snap, Facebook has other things on its mind at the moment.

Facebook’s multiple battle fronts

If there was a perfect time for Snap to stage its counterattack against Facebook/Instagram, it’s now, while the Book is inundated by the war on Fake News and the battle for Time Well Spent.

So far, it’s been confirmed that Russian agents paid Facebook $100,000 for about 3,000 ads aimed at influencing American politics around the time of the 2016 election. Meanwhile, a Russian agency called the Internet Research Agency created pages and groups to sway political opinion in America (e.g. Heart of Texas, Blacktivist). An examination of 500 posts from a collection of groups has been shared more than 340 million times.

On a second front, “Time Well Spent” activists Tristan Harris and Roger McNamee are making the federal, state, and media rounds, attempting to hold Facebook, Twitter, and Google accountable. Harris recommended that the CEOs of the companies be called in front the House and Senate Intelligence Committees at hearings about Russian interference. McNamee went on a media tour, putting Facebook on blast in The Washington Post and The Guardian for gross manipulation of users.

Finally, in a fight closer to home, former high-ranking Facebook executives have come out publicly against the company. On November 8, 2017, Facebook’s first president, Sean Parker, said he now regretted pushing Facebook so hard.

“I don’t know if I really understood the consequences of what I was saying,” he said. “God only knows what it’s doing to our children’s brains.”

Facebook’s former privacy manager, Sandy Parakilas, called for government regulation in an NYT op-ed: “The company won’t protect us by itself, and nothing less than our democracy is at stake.”

And Chamath Palihapitiya, Facebook’s former VP of Growth, who introduced the “7 friends in 10 days” Aha Moment metric, said products like Facebook “created tools that are ripping apart the social fabric.” And he feels “tremendous guilt” for his role in that.[note]Wired Magazine – Feb. 12, 2018 | Inside the Two Years that Shook Facebook–And the World – https://goo.gl/G8ZnHR[/note]

Snap vs Facebook isn’t just a product battle

Product innovation seems to be the tip of the spear in the Snap versus Facebook/Instagram battle, but it’s certainly not their only weapon. We don’t have to look far back in history to see how smaller companies won against entrenched incumbents, and it wasn’t just by being faster, stronger, and better.

In the 1870s, the small telephone company, Bell, went to war with the giant telegraph company Western Union over the future of the medium that first heralded a connected world: the telephone.

Western Union looked unbeatable: a mountain of capital, existing relationships with the media and politicians, and most importantly, a fully developed network of wires already stretching across America that it used to send messages via the telegraph. On top of that, they were also in the product innovation game, hiring a young inventor by the name of Thomas Edison to improve on the machine that Alexander Graham Bell (of Bell Telephone Company) invented.

Despite these advantages, Western Union lost the telephone war. How?

In a name: Jay Gould.

Jay Gould was a financier who quietly acquired Western Union stock while the company was engaged in the battle for the telephone. In 1878, he attempted a hostile takeover, and out of self-preservation, Western Union pulled back from the front lines of the telephone war. Thanks to Gould’s blindside attack, the general manager of Bell Telephone Company, Theodore Vail, struck a hard bargain: in exchange for 20 percent rental income on the new Edison telephone, Western Union agreed to abandon the telephone game forever, and Bell promised never to enter the telegraph market.

History has shown what a miscalculation that was, as the telephone went on to kill the telegraph anyway, ending Western Union’s dominance in business, media, and politics. Meanwhile, Bell went from strength to strength, eventually changing names to the American Telephone & Telegraph Company, aka AT&T.[note]The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires by Tim Wu | pg. 31[/note]

Or we can look at the birth of another fledgling medium and industry: film.

By 1912, a single conglomerate called the Film Trust based in New York City owned the film patents, controlled theaters and film distribution, and possessed the “first mover advantage” over the rest of the industry.

Yet it was a determined group of producers, mostly immigrants, by the names of Zukor, Laemmle, Fox, and Warner, who managed to wrestle control away from the trust, head west to create Hollywood and the film industry we know today. How?

What this group of producers lacked in technical know-how, they made up for in taste. It was a young, urban audience attending these films — an audience the producers had themselves come from. The producers funded ambitious projects, driven by the director’s vision, that people actually wanted to see. Meanwhile, due to the Trust’s system of fixed prices and capped budgets, they continued to put out the same bland product.

“What they were making belonged entirely to technicians. What I was talking about — that was show business,” Zukor said.

This group of producers went on to become the moguls of Hollywood itself, building studios that would dominate film for years: Paramount, Universal, 20th Century Fox, and Warner Bros.[note]The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires by Tim Wu | pg. 72[/note]

History shows that given the right circumstances, the underdog can beat the incumbent. Snap can still beat Facebook by exploiting a number opportunities:

- Cracking the context code. Continue to be the communication platform where users feel like they can be themselves.

-

Taking advantage of an entrenched Facebook. Strike while Facebook is inundated with fake news and time poorly spent allegations.

-

Giving users the experience they actually want. Snap can’t just be the “cool” platform anymore. It needs to build products the audience actually wants to use.

###

Photo Credit: Patrik Nygren