The assistant next to me, Katie, worked for the hardest working executive in the office. By extension, that made her the hardest working assistant. She was smart, excellent with clients, and beautiful (she was an ex-Ford model).

She was also the worst paid.

“Are you fucking joking?” she whispered.

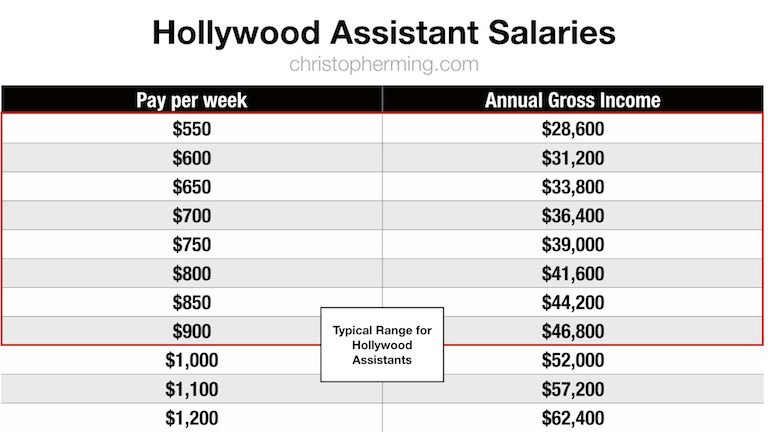

I showed her the breakdown of our salaries. As an assistant, your salary is calculated on a weekly basis, probably because it’s too depressing to convert that to an annual salary.

“You’re here. I make $750. Michael makes this, and Crystal makes this.”

“How did you find this out?” she asked.

“I ask,” I said.

“You deserve what you make. But Crystal, I mean, her boss is never even here! She doesn’t have to do anything!”

Katie paused.

“Goddamnit, I have to ask for a raise.”

This is the story that plays out for Hollywood assistants in Santa Monica to Sherman Oaks. It’s the eternal battle to scratch together a salary you can live on. Which wouldn’t be so terrible if not for the wage disparity between assistants and their executives.

For example, I used to earn $600 per week as a casting assistant: setup the office, create breakdowns, schedule actors, manage the room, manage the casting director’s schedule, and take notes. Meanwhile, one of my directors never arrived on time, couldn’t figure out Breakdown Express, couldn’t read with actors… and made $3,000 per week.

That’s the game though, and you endure, because whether you’re:

- An assistant trying to become an executive

- A writer’s assistant trying to become a showrunner

- An actor trying to become a star

You believe that if you put in the time, eventually you’ll make it to the next level. And then the level above that. Climbing higher and higher, until you reach an echelon where you can finally enjoy the fruits of your struggle.

I imagine that’s how Michelle Williams felt about her career. After 20 years of climbing, I imagine she felt like she’d paid her dues, and had now assembled a team of representatives (agents, lawyers, manager) to protect her career interests.

So when the story about Kevin Spacey’s years of harassment broke, and Ridley Scott asked her to do reshoots for free, Ms. Williams didn’t hesitate.

“I said I’d be wherever they needed me, whenever they needed me. And they could have my salary, they could have my holiday, whatever they wanted. Because I appreciated so much that they were making this massive effort.”

So Ms. Williams explained to her daughter why she had to be gone during Thanksgiving, and she flew out to work, for free, in a display of solidarity.

How did Ms. Williams feel a month later, when her phone started blowing up, the tweets started pouring in, and USA Today broke the story that her co-star, Mark Wahlberg, earned $1,500,000 for those same reshoots? How did it feel that at the height of her career, with one Golden Globe, four Academy Award nominations, and one Tony Award nomination, she STILL has to fight for her salary, and she STILL can’t count on her “team” to protect her best interests?

Her agents dropped the ball. She should drop them

Michelle Williams didn’t know her co-star earned $1,500,000 for the reshoots while she earned her $1,000 per diem. Then again, it’s not her job to know. That’s her agents, Brent Morley and Patrick Whitesell’s job. Their duties can be distilled down to a single sentence: Protect the client.

More specifically, make deals that maximize upside and protect downside. The difference between a good and bad agent is measured in degrees of how far one will go to do this. The five founders of the Creative Artists Agency were thrown out of the William Morris Agency in 1975 when word got out they were planning on leaving. They worked on card tables. Their wives took turns being the receptionist. In 1995 founders of Endeavor tried stealing files out of International Creative Management in the middle of the night. They got caught and publicly humiliated.

Stars’ agents went to any lengths just to break into the industry. David Geffen steamed open envelopes from UCLA and CBS, and fabricated confirmations and recommendations on fake stationery to work at WMA. Jack Rapke broke up with his girlfriend and did nothing on weekends except work and laundry to get into WMA. Adriana Alberghetti, the first trainee out of the Endeavor mailroom, gave up a cushy job at Smith Barney to make $21,000 delivering mail and answering phones.[note]The Mailroom by David Resin[/note]

In the case of Ms. Williams, however, no one needed to stoop to nefarious means to protect her interests. No one had to steal files, or break into offices. They didn’t even have to ask the valet to pull up their cars to leave 9601 Wilshire Blvd.

All Mr. Moley had to do was get up, walk to Doug Lucterhand or Rich Cook’s office and ask, “Hey, what’s Wahlberg making for these reshoots?”

Williams and Wahlberg are represented by the same agency.

There are a couple of arguments defending the agency, explaining why this conversation never took place between the agents:

- Williams was contractually obligated for the reshoots, while Walhberg was not

- Agents aren’t supposed to discuss their client’s deal terms with one another

Neither make sense. Let’s look at why.

Williams was Contractually Obligated for the Reshoots, Walhberg was not

This argument implies because Williams was contractually obligated, she had no choice but to participate in the reshoots. Wahlberg, on the other hand, had the option to participate. The argument misses the moral and philosophical point.

In this situation, the real difference between the two actors was leverage. Williams had no leverage, because reshoots were in her contract in exchange for an agreed upon salary. She didn’t have the leverage to ask for more money, which is moot since she deferred her salary anyway. On the other hand, Walhberg was NOT contractually obligated. This gave his representation leverage to extract a large fee for the reshoots, leverage they applied, even though they knew Williams and Scott deferred their salaries.

Had these been ordinary circumstances, Wahlberg’s agents and WME would have done nothing wrong. They took advantage of the situation to make a better deal, in the best interest of their client. However, given that Williams and Scott deferred their salaries for reshoots, it feels exploitative for Wahlberg’s agents to have used these reshoots (brought about by allegations of sexual assault against Kevin Spacey who had originally starred alongside Williams & Walberg) to earn an extra payday for their client.

Agents Aren’t Supposed to Discuss Client’s Deal Terms with One Another

According to TMZ, agents advocate for their individual clients and have a duty of confidentiality not to disclose to one actor what another is getting paid. [note]https://goo.gl/6Fj6TN[/note]

First, agents don’t have to disclose actor salaries to other actors, but they can certainly disclose this information to other agents. Sharing deal notes is how they increase an actor’s quote, learn how hard they can push specific studios, and make the agency more money.

Second, typically it’s not just one agent covering an A-list client like Williams or Wahlberg, but a team of agents. There are senior agents, who sign the client and then only step in on occasion. Then there are covering agents, who handle the day-to-day business for the clients.

Williams’s senior agent is Patrick Whitesell. Wahlberg’s senior agent is Ari Emanuel. Both are Co-CEOs of WME-IMG. As mentioned above, it’s unlikely either are involved in the day-to-day, but it’s also unlikely that Williams’s team had no idea Wahlberg was making $1,500,000 for his reshoots while she deferred her salary.

Let’s talk about why this happened, and how Williams found herself in a position of making nothing while her co-star took home a fat paycheck. It boils down to two reasons:

- The Hollywood quote system

- The difference between a star and an actor

Let’s break those down.

The Hollywood Quote System

Most Hollywood salaries work off of a quote system, whether you’re a writer, director, or actor, whether you’re working in movies or television. Offers are based on the budget of the production, the size of the role, AND how much you made on your last project.

This creates a double-whammy for female actors. More productions feature a male protagonist, limiting a woman’s salary based on the size of the role. The knife stabs a second time because she gets fewer opportunities to increase her quote.

“I can’t get a small role in an indie,” Elizabeth Banks said, explaining why ultimately she looked towards producing instead of just acting. [Her friend] Paul Rudd, gets “70 percent more at-bats than I do. He has that many more chances to improve his quote.

“There’s a lot of material that stars men between the ages of 20 and 50. There is not that amount of material for all of us actresses.”[note]New York Times – Dec. 20, 2017 | Elizabeth Banks Was a Frustrated Actress. Now She’s a Determined Mogul – https://goo.gl/CLXN91[/note]

So actors like Jennifer Lawrence might discover after the fact that they were paid less than their co-stars, because at the time they didn’t want to be difficult.

“I would be lying if I didn’t say there was an element of wanting to be liked that influenced my decision to close the deal without a real fight. I didn’t want to seem ‘difficult’ or ‘spoiled.’ At the time, that seemed like a fine idea, until I saw the payroll on the Internet and realized every man I was working with definitely didn’t worry about being ‘difficult’ or ‘spoiled.’ [note]Lenny October 13, 2015 | Letter No. 3 – https://goo.gl/QZaHhq[/note]

(On the rare occasion, male co-stars will take a salary cut for their female co-star, as Emma Stone noted in an interview with Out Magazine. “In my career so far, I’ve needed my male co-stars to take a pay cut so that I may have parity with them. And that’s something they do for me because they feel it’s what’s right and fair.”)

Difference Between a Star and Actor

I personally believe Michelle Williams is one of the greatest actors in my generation. She’s incredible and heartbreaking to watch in films like Shutter Island, Brokeback Mountain, and Blue Valentine, to name a few.

Mark Wahlberg — again, in my opinion — is at his best when he plays Mark Wahlberg. It’s not that he doesn’t have layers — he’s displayed that in The Fighter and Pain & Gain. But he’s just more fun to watch him as Sgt. Sean Dignam in The Departed or, well, Mark Wahlberg in Entourage.

Which is precisely that reason that Ms. Williams is one of the best actors in Hollywood, while Mr. Wahlberg is one of the most well-paid stars.

Sylvester Stallone put it this way to Ronda Rousey when explaining the difference between actors and stars:

“The greatest actors aren’t the biggest stars. A great actor can play anyone in any situation, but you don’t see people lining up around the block to see most critically adored actors.

“You see people lining up around the block to see stars like Al Pacino, who in every role is himself. He doesn’t play different people. He’s Al Pacino as the cop. Al Pacino as the lawyer. Al Pacino as the gangster. Al Pacino as the blind retired Marine or whatever. He always plays himself, and people just fall in love with that character of you. That’s what makes you a star.

“That’s what makes people line up around the block.”[note]My Fight/Your Fight by Ronda Rousey[/note]

So the Hollywood quote system and the difference between an actor and a star are two of the tectonic plates of Hollywood that caused the Williams/Wahlberg situation. But some women ARE able to land massive deals, mostly in television.

Next, let’s look at one such deal and how it came together.

The Ellen Pompeo Deal

“I was like, ‘I’m not going to be stuck on a medical show for five years. Are you out of your fuckin’ mind? I’m an actress.'”

Probably not what you’d expect to hear from an actor — especially one who just locked in one of the most lucrative deals in television. But that’s how Ellen Pompeo reacted when her agent brought her the pilot script to a show called Grey’s Anatomy.

Now, 14 seasons later, and just two weeks after USA Today broke the story about Ms. William’s salary, The Hollywood Reporter published an exclusive interview with Ms. Pompeo and her monster deal with Disney/ABC.

It’s rare you’ll ever get the full details of a deal this magnitude (for example, her mentor and boss, Shonda Rhimes, remains mum about the details of her Netflix deal) but THR revealed the nuts and bolts of the Ellen Pompeo deal. Ms. Pompeo also discussed how the departure of her co-star Patrick Dempsey played into the negotiations of making the deal:

“Pompeo’s new pact will have her earning more than $20 million a year — $575,000 per episode, along with a seven-figure signing bonus and two full backend equity points on the series, estimated to bring in another $6 million to $7 million. She also will get a producing fee plus backend on this spring’s Grey’s spinoff as well as put pilot commitments and office space for her Calamity Jane production company on Disney’s Burbank lot. Already, she has a legal drama in contention at ABC, and she recently sold an anthology drama to Amazon, which will focus each season on a different American fashion designer’s rise to prominence.”

To appreciate the landmark-ness of the deal, we’ll break it down and analyze the parts:

“Pompeo’s new pact will have her earning more than $20 million a year…”

A pact is simply a deal with a studio. And while $575,000 per episode IS a lot of money, it’s a far cry from the best deal out there for a female actor. Kaley Cuoco makes $1,000,000 per episode on The Big Bang Theory, which airs 24 episodes per season.[note]Mic – Mar 1, 2017 | How much money does the cast of ‘The Big Bang Theory’ make? – https://goo.gl/9wfM2N[/note] Meanwhile, Emilia Clarke, aka Daenerys Stormborn of the House Targaryen, First of Her Name, the Unburnt, Queen of the Andals and the First Men, Khaleesi of the Great Grass Sea, Breaker of Chains, and Mother of Dragons, makes $500,000 per episode on Game Of Thrones (and shoots far fewer episodes.)[note]Variety – Aug. 22, 2017 | TV Salaries Revealed, From Ellen DeGeneres to Katy Perry and The Rock – https://goo.gl/XegCdH[/note]

“along with a seven-figure signing bonus…”

The signing bonus is a double-edged sword. Ms. Pompeo gets more money upfront, however, it doesn’t factor into her per-episode quote of $575,000.

“two full backend equity points on the series…”

This is pretty ambiguous since there are many different definitions of backend equity. One definition could be worth millions, while another could be worthless. For example, compare the difference between Net Profits vs. Adjusted Gross Receipts.

Net Profits means you participate in profits after full studio distribution fees on revenues, all distribution expenses, including OTT’s and advertising overhead, studio overhead, interest on unrecouped negative cost, and so on. In other words, thanks to Hollywood’s accounting magic you’re never going to see a check.

Meanwhile, Adjusted Gross Receipts, or AGR, is equal to gross receipts less OTT.[note]USC Marshall School of Business – https://goo.gl/Gpt76v[/note] The bottom line: AGR participants are almost guaranteed to see a significant payday on a successful show because they get an early piece of the pie.

“She also will get a producing fee plus backend on this spring’s Grey’s spinoff…”

Any participation in spinoff programming is reserved for producers and high-level actors.

“as well as put pilot commitments…”

A put pilot commitment means the network preemptively agrees to air a pilot episode. If they don’t, they’ll pay a penalty to the studio. Basically, Pompeo gets a guarantee that any show she produces will at least air a pilot. However, that is not a commitment to a full series order.

“and office space for her Calamity Jane production company on Disney’s Burbank lot…”

Um, office space.

Just to drive the point home: This Ellen Pompeo deal is a monster. How does a deal like this come together?

It required a perfect storm of conditions.

The Ellen Pompeo deal benefited from a number of perfect conditions to put a deal together like this, including:

- The mentorship of Shonda Rhimes. Ms. Rhimes helped her learn how to ask for what she was worth

- Rhimes leaving Disney/ABC for Netflix. Now, more than ever, Disney/ABC needed to protect existing Shondaland properties

- Patrick Dempsey leaving Grey’s. This left Ms. Pompeo as the only remaining star from the original cast, improving her leverage

- Disney/ABC’s acquisition of Fox. This was costly, and they needed their cash cows to continue to produce, like Grey’s

By making this deal, Pompeo secured her place in Hollywood, a place where there’s little security for women.

“I’m not necessarily perceived as successful,” Pompeo said. “But a 24-year-old actress with a few big movies is, even though she’s probably being paid shit — certainly less than her male co-star and probably with no backend. And they’re going to pimp her out until she’s 33 or 34 and then she’s out like yesterday’s trash, and then what does she have to take care of herself?”

Without being abjectly cruel — no need to name names — we can all probably recall a time where we thought about a particular actor and wondered, “Whatever happened to them?” This says less about anyone’s talent, and more about the capriciousness of the industry itself, where today’s stars are tomorrow’s “trash.”

This is the business that women and men like Michelle Williams, Mark Wahlberg, and Ellen Pompeo are in. There’s a shelf life, and whether you’re a man or a woman, it’s unpredictable. If you’re on the wrong side of politics, a late adopter of technology, or you’re picking the wrong projects, you too will be forgotten.

As an example of this, we come full circle in our story, to the actor whose behavior kicked off the necessity to reshoot scenes of All The Money In The World: Kevin Spacey.

The Capriciousness of Hollywood

Mr. Spacey had an incredible first act in Hollywood, co-starring in The Usual Suspects in 1995, winning an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor. In 1997, he co-starred in L.A. Confidential, which won two Oscars. And in 1999, he starred in American Beauty. American Beauty went on to win Oscars in five categories, including Best Actor for Spacey.

After American Beauty, Spacey’s star dimmed for a considerable time. According to the head of Spacey’s production company and his former assistant, Dana Brunetti, there was a series of miscommunications that led to Mr. Spacey doing a series of movies they both hated.

“I would send these scripts to Kevin to get his feedback on it. And he’d be like, ‘Yeah, that’s great. We should do it.’ And so I’d be like, ‘O.K.’ And I’d put all my force behind it, and I would get these projects made. And … they sucked.”

Mr. Brunetti discussed the matter with Spacey, and complained about their recent projects. Spacey admitted he hated the projects as well.

“Why the fuck then did you say let’s do it and that you liked it?” asked Brunetti

“I thought you liked it, and I was just trying to be supportive of you,” said Spacey.

“Are you fucking kidding me?”

From that moment on, Spacey told him, Brunetti had the freedom to run the company as he wanted.

With that freedom, one of the projects Mr. Brunetti put in front of Spacey to produce was a book called The Accidental Billionaires. That movie became The Social Network.

Later, he brought him another project, this one based on a British mini-series. The mini-series was called House Of Cards, and he took it to Netflix. Spacey was confused. “Wait, so we’re going to do this on DVD?”

Mr. Brunetti talked him into it, and Spacey said to director David Fincher, “Well, Dana’s saying do it. Let’s do it.” And so Kevin Spacey enjoyed his continuing rise to stardom, including a whole new echelon of success, matched only by the second coming of his co-star, Robin Wright’s, career… until the allegations of sexual harassment came out against him.[note]Feb. 2016 – Vanity Fair | Dana Brunetti, Hollywood’s Most Openly Disliked and Secretly Beloved Executive – https://goo.gl/FFBbWN[/note]

The moral of the story: stars fizzle, even (especially?) the ones that burn the brightest. So how do women in film and television, who play in this well-documented rigged game, make the most of their stardom? How do they get their Sheryl Sandberg on and “lean in?”

What a difficult balance to strike, especially in the nascent years of the journey. You’re just grateful for the work and the recognition. You don’t want to seem “spoiled,” as Ms. Lawrence noted.

Even for someone like Shonda Rhimes, there was a learning curve. “I’ve had to learn not to get screwed in this town,” she said. Grey’s was the first TV series she created. “Imagine the deal (terms) on the first television show you ever made,” she said.[note]Oct. 4, 2017 – Variety | Shonda Rhimes Talks Netflix Deal, Shondaland Digital Venture and Inclusion vs. Diversity – https://goo.gl/5zTsJo[/note]

(An important caveat: By no means does every artist, man or woman, have to adhere to the Shonda Rhimes’ playbook. That’s not what I’m saying. Some actors just want to act. Some writers just want to write. They don’t want to to get involved in the game at all. And if it makes them happy, and they can make a living, then… amazing. That is an incredibly fulfilling life.

But if they want more, if they want a better seat at the table, then it’s worth paying attention to the way Williams, Rhimes, Banks and Pompeo navigate the landscape.)

If we assume that we will continue to see rigged games not just in Hollywood, but spanning across industries and that every person will have to continue to battle to get paid what they’re worth, I see three takeaways from these women’s stories:

1. First, accept reality. Everyone has a shelf life. The game is rigged. Deal with it.

2. Understand how you fit in the game. Only when you understand your role can you expand it, or find other areas to add value.

3. Create value, then leverage it. No one is handed anything. The only way to earn what you’re worth is bring more to the table, then demand to get paid fairly for it.

###

Special thanks to Jeff Girten, who helped me think through contractual obligations on talent deals.