We sold this house and moved to Dublin, Ireland. Most of these lessons have held up, but living in the house for 3 years developed my thinking in other ways.

TL;DR we weren’t ready for a move to the suburbs. We missed the energy and walkability of the city. I believe your environment — the people and places you surround yourself with — quietly shape you. You can resist the change but you’re fighting upstream the entire time. Someday we may be ready to be molded into archetypal “suburban parents”. Just not yet.

So at the peak of this crazy post-pandemic market, we sold the house at a loss to my brother and his girlfriend, packed our things into 7 large suitcases, and moved to Dublin.

New lessons learned:

1. Go all-in on your decisions

Just because we moved after 3 years doesn’t mean the move was the wrong decision.

I strongly believe moving to the suburbs was the right decision.

When we moved, there were a few hypotheses to validate:

- We would enjoy the process of homeownership, e.g. decorating, house projects, etc.

- We would enoy the convenience of driving everywhere

- We could still progress in our careers

Unfortunately, we disproved these hypotheses, among others; I spent more time organizing my house projects Trello board than doing actual projects. We missed walking to bars and coffee shops. And working remotely, far away from the hubs of our industries, meant there were few opportunities for serendipitous meetings or shop talk.

Committing by buying a house gave us the best shot at success. If we hedged out bet by renting or buying a house we didn’t love, we’d have less confidence in the result. Because we went all-in on the decision, we’re confident that Albany wasn’t the right fit at this moment, and can move forward without second-guessing ourselves.

Going all-in is the best way to avoid uncertainty.

2. Decide what you are optimizing for

If we were optimizing for financial security, we’d stay put in Albany.

Low cost of living, low taxes, etc. Bank the newfound equity thanks to this housing market, and make stacks on stacks. It’s a smart play.

Until you have a degree of financial security you’re comfortable with (different for everyone!) that’s what you should optimize for. I always kept financial security in the back of my mind, even when taking bigger life “risks”.

For example, when I moved to Los Angeles with no job and no prospects, I still found ways to optimize for financial security. I took on 2 roommates to keep rent low. I got a restaurant job my first week there. I minimized risk as much as I could.

Once you have financial security though, it doesn’t make sense to make it your first priority anymore. You can invest in other vectors of your life.

What are we optimizing for in Dublin? In a word, I think: “adventure.” We’ve talked about doing this move for 10 years. We wanted to get back to an urban lifestyle.

We’re optimizing for a new adventure for our family over maxing out our IRAs.

3. Do a 30-year mortgage, not 15-year

This is a bit more tactical but equally important: we did a 15-year mortgage. That was a mistake.

A 30-year mortgage can be turned into a 15-year mortgage. Just (roughly) double your monthly payment. But it’s an expensive alchemy to transform a 15-year mortgage into a 30-year.

Going into the house buying process, I had an immigrant money mindset: remove debt from the ledger ASAP and incur the least amount of interest as possible. That’s not necessarily the optimal strategy, however, because:

- Opportunity cost. I paid an extra $1,200 each month to pay down a low-interest rate loan. That $1,200 could have gone towards investment opportunities that outpaced the interest rate.

- Time horizon. The math of saving thousands of dollars on interest payments only starts to work around the 5-year mark. If you sell before, the benefit is minimal to non-existent.

- Black swans. Unpredictable events (like a global pandemic) can threaten your job and cash flow. Your model to calculate your nut goes out the window, and now you have to scramble to bridge the gap.

4. If it’s not working, change it

Lastly, if something’s not working, then it’s your responsibility to change it.[efn_note]I’m mostly talking about decisions you’ve made: jobs accepted, relationships started, cities chosen. Obviously, there are difficult uncontrollable circumstances where change is more difficult.[/efn_note]

We all make the best decisions we can with the information we have at the time. Sometimes, we make the wrong one. Don’t complain; get to work reversing it.

Your life is short; your time is valuable. Don’t hold yourself hostage to past decisions.

—

First published: 2018.06.01

Growing up I wanted to live in a RV (still do, if I’m honest).

Until I started considering a move (back) to Albany, I never thought I’d look for a house or apply for a mortgage (except as a rental property in Ireland).

Having closed on a house recently, here are some things I learned about the process that might make it easier for you:

- Ask, “Why do I want to buy a house?”

- Run your numbers

- Get quotes from at least 3 different lenders

- Make apple-to-apple comparisons

- Ballpark your initial and recurring costs

- Expect the closing costs to surprise you

(Note: Definitely consult with experts before buying your home. I am not an expert, I hire others to help with my finances. These are just notes from my personal experience.)

Ask, “Why do I want to buy a house?”

Before anything else, let’s return to First Principles: Why do you want to buy a house?

There are good reasons to buy a house. Unfortunately, there are bad ones, too. Let’s start with those:

- Your friends are doing it

- You’re 30-years-old and you’re supposed to

- You’re sick of wasting money on rent

You are not your friends. You don’t “have” to buy a home, ever. And this “wasting money on rent” myth is one of the greatest fabrications created by banks (the financial institutions that created a financial product (the mortgage) to sell you for a significant return on their investment).

I love renting. I’d be thrilled to rent for the rest of my life.

So why buy a home?

When I started a family, I wanted my children to grow up with a strong support system. I wanted them to have a sense of roots. That meant moving back to my hometown so they’d be surrounded by family. Buying a home made sense at this point in my life, and fortunately, we could make it work financially.

Because another big mistake we make is thinking about the house as an “investment.”

The house you live in is not an investment vehicle, because it doesn’t generate income. It’s just a place to live. Buying a house is a lifestyle choice, not an investment strategy.

Get quotes from at least 3 different lenders

Shop around. Lenders can differentiate themselves in many ways. Some will loan at slightly different rates, depending on your credit score. If you’re not putting 20% down, they’ll offer different rates on the PMI (private mortgage insurance).

Even the mortgage product itself can be quite different. For example, one lender had a mortgage that included a one-time drop down rate, meaning if the interest rates went down, you could lower your rate once over the life of the loan.

How responsive are your lenders? How fast do they return calls or emails?

Is there a pre-pay penalty? In other words, you want the option to pay more than the monthly payment, which you can specify you’d like directly applied to the principle.

Are the lenders in the area where you’re buying the house? There’s leg work involved, especially on closing day, so you want everyone in close proximity in case a check or form needs to be recut or rewritten.

Also, when you’re in the process of getting quotes, keep a list of all the documents you’ll need to close (previous addresses, bank statements from the last month, two of your most recent paychecks, letter from employer that I work remotely, etc.) Keep these all in a single folder so you can get them over to lenders as quickly as possible.

Run your numbers

All the lenders I met were super nice people. If we grabbed a drink, I’m sure they’d be great company.

I’m equally sure they’d tell me the sun shined from my ass if it meant I’d borrow their money.

Lenders are in the business of making the best return on their investment. To do that, they are within their right to loan the full amount that a potential buyer is approved for, even if their monthly cash flow post-tax is only enough to cover principle and interest, or their meager savings aren’t enough to cover the closing costs. If you can’t find the funds to cover the closing costs, you can tack on additional funds to cover that, as well.

I’m not saying there’s a nefarious scheme at work here. I’m saying you and the lender have different incentives. You’re trying to get the best rate and make the monthly nut. They’re trying to extract the most value from you over the longest period of time.

That’s why it’s your responsibility to run your own numbers.

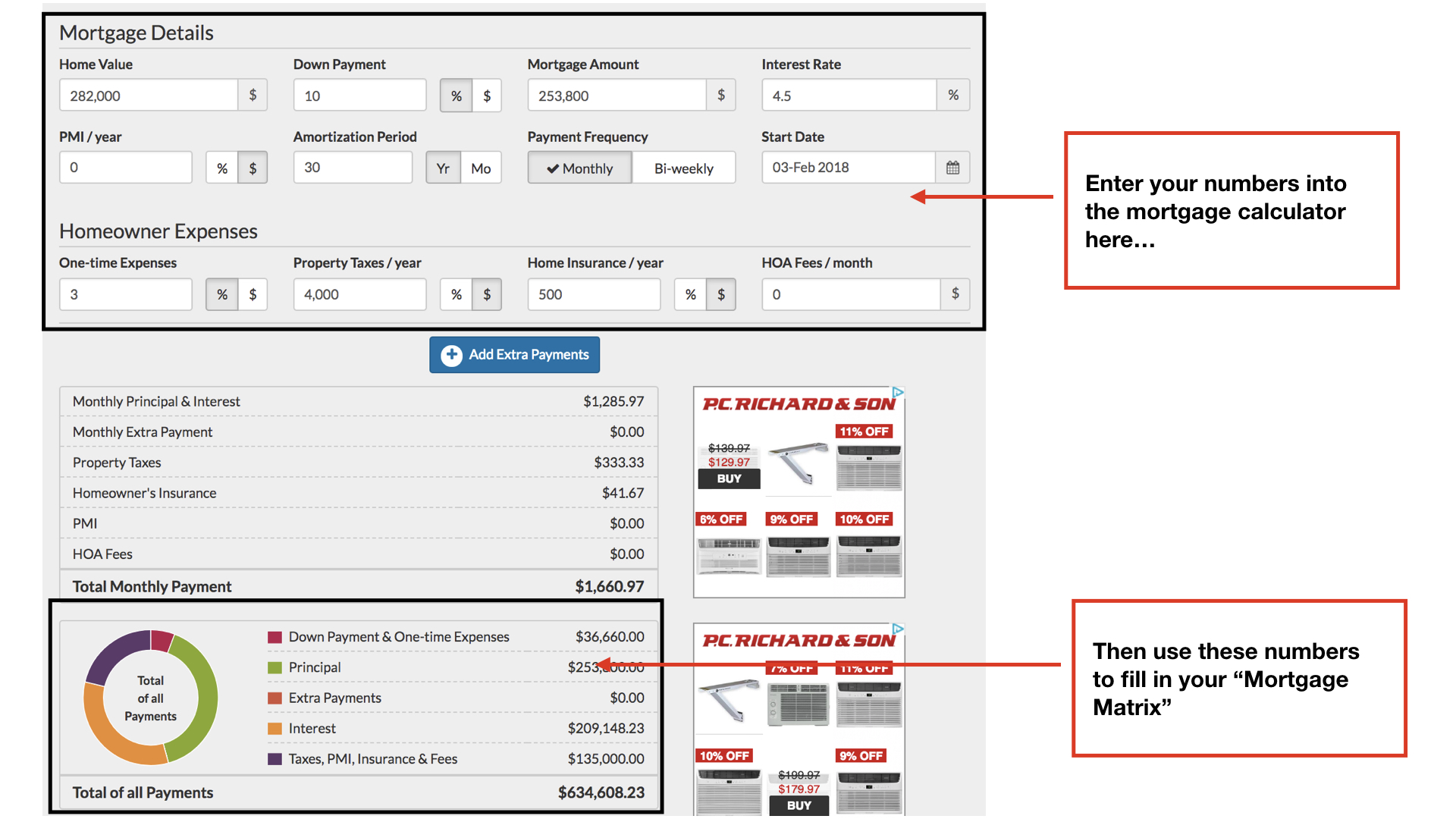

There are plenty of free mortgage calculators online that will help you break down any of the numbers you get back from the lender ( IMO this is the best one). Instead of taking the numbers at face value, run them yourself so you can compare not only the principle and interest, but also the total payment over the life of the loan.

(I talk about that more below.)

Make apple-to-apple comparisons

Once you get quotes from different lenders, make sure everyone’s speaking the same language.

Some quotes might include a lock-in fee or the PMI. Others will only give you the principal and interest payment and exclude property taxes and insurance. No one will tell you the total of all payments for the life of the loan unless you ask.

Plus, you should consider the implications of both a 30 year vs. a 15 year mortgage, and a 20% down payment versus a 10% down payment.

The only way to get clarity is to run your own numbers and get to an apples-to-apples comparison.

Here are the 5 steps you can take to get apples-to-apples:

1. Pick 3 lenders you think you’d like to work with

Write down the qualitative pros and cons of each, for example:

- “He’s nice”

- “She’s really responsive on email”

- “This lender is right across from the house”

2. Will you put down 20% or 10% for the down payment?

Using the numbers from just ONE of the lenders, run the numbers with all else being equal except for the down payment. Here are some of the things you’ll notice:

- With 10% down, closing costs will be significantly lower

- With 10% down, your monthly payment will be higher

- With 10% down, you have to include the annual PMI, which gets added to the monthly payment (until you’ve paid back 20% of the principle)

- With 10% down, you can invest the other 10% and might (on paper) see a better return on your money (play around with an interest calculator to see what the numbers look like — I recommend this one). For example, I did a break even analysis and saw that I only needed a 2% return on the market to make it worthwhile to invest the other 10%, rather than use it as a down payment.

Decide which one is right for you depending on your financial situation.

3. Will you do a 30-year mortgage or a 15-year mortgage?

Using the numbers from the SAME lender, run the numbers with all else being equal except the life of the mortgage. Some of the differences you’ll notice:

- With a 15-year mortgage, your monthly payment will be significantly higher

- With a 15-year mortgage, your total payment will be significantly lower

Decide which one is right for you depending on your financial situation.

Note: I’m not recommending 10% down or a 15-year mortgage. Just using those numbers as baselines for this comparison.

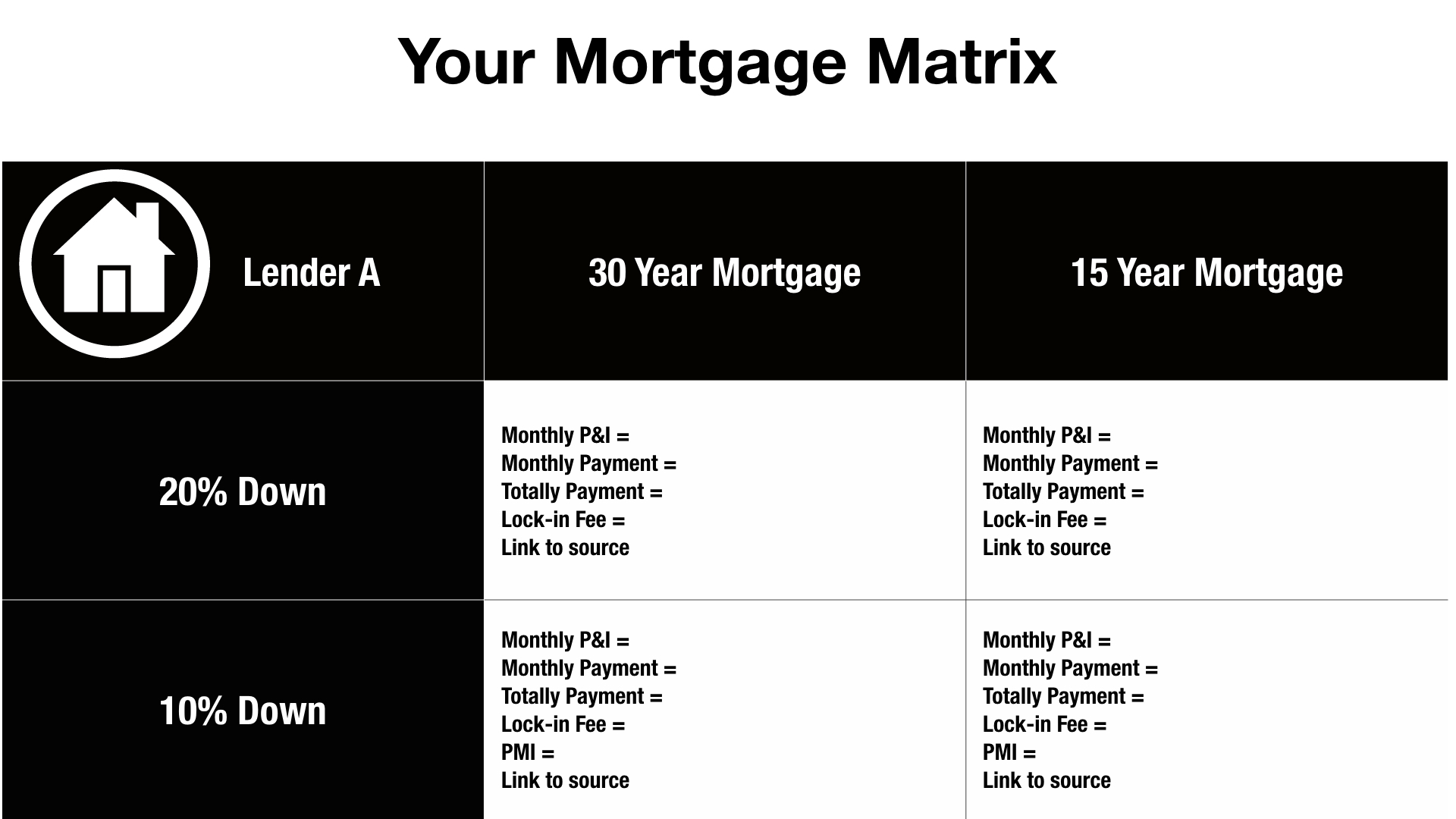

4. Put all the numbers into a matrix

Now you know which combination of down payment and life of mortgage makes the most sense, we can determine which lender is giving you the best deal.

Within each cell, you’ll want to include:

- Monthly principle and interest

- Monthly payment

- Total payment

- Lock-in fee (if any)

- PMI (if any)

- Link to the source (in case you want to double-check your work)

(See above for an example of what your house matrix could look like.)

Next, use the mortgage calculator and get all your numbers.

When you’re done, you’ll have an apples-to-apples comparison between all the lenders.

5. Look at the lenders quantitatively and qualitatively and make your pick

Quantitatively, you just want to pick the lender that’s giving you the best deal. Because you’ve done the work in steps 2 and 3, you know which loan is best for you (e.g. 15-year mortgage at 20% down).

Qualitatively, go back to your notes. Can you see yourself working with this lender? Any red flags you noticed in your communication back and forth?

This can be tricky to figure, so I started a Mortgage Matrix for you in this document. Just go to “File > Make a copy” to create your own copy.

Ballpark your initial and recurring costs

When I moved from Los Angeles to New York City, none of my old furniture came with me. And in NYC, I’ve gotten by with pretty minimal furnishings.

Now there’s this entire house that needs renovations, rooms that need furniture, and oh yeah, this baby that may like a place to sleep, too.

Here are some of the initial costs I’m looking at:

- Moving – $1,900

- Renovations – $3,300

- Bedroom set – $1,600

- Sofa – $1,000

- Mattress – $1,200

- Dining room table – $610

- Dining room chairs – $360

Then, there are monthly recurring costs that you need to add to your monthly mortgage payment (principle, interest, PMI, taxes) Here are some:

- Internet – $100

- Gas – $75

- Electric – $75

- Lawn maintenance – $50

- Garbage pickup – $50

- Security alarm – $100

Expect the closing costs to surprise you

I knew the cash to close was going to be more than I thought — and it still surprised me.

There are a ton of fees that get added on. You can look into the nature of all these fees and whether they’re something you can avoid. Personally, I’d rather pay a lawyer an additional fee to just make sure everything’s covered and fair, then get on with my life.

It’s easy to get so caught up in the process, you forget you need a huge chunk of money to close the deal. The payment needs to be a cashier’s check, and they’ll let you know the final amount a day or two before the closing. Just make sure you have the money in a bank account beforehand, and there’s a local branch nearby where you can get the cashier’s check.

Conclusion

Buying a house is a huge personal and financial decision. There are a lot of resources out there to help you, but remember, ultimately you’re responsible for running your own numbers.

###

Photo Credit: Jonathan Andreo, Eduard Militaru, Charles Deluvio, Mathyas Kurmann

1 Comment

Pingback: Lessons from my second real estate investment | Christopher Ming Blog