Olivia de Havilland was 19-years-old when she started her acting career. Eight years later, she killed the Golden Age of Hollywood and changed the business of entertainment forever.

In the 1930s and 40s, studios could “suspend” an actor for a number of transgressions, then tack that time back onto an actor’s multiyear contract. Most actors went along with it, rather than be blacklisted by the studios.

When Warner Brothers tried adding six months onto Ms. de Havilland’s contract for time suspended, she took them to court, and won. Employers could no longer enforce a contract for longer than seven years, and the law became known as De Havilland Law. This forever nerfed the power of Hollywood studios and the men whose names graced the front door (Mayer of MGM, Warner of Warner Bros, Zukor of Paramount, and Zanuck of Fox).

For her contribution, Ms. de Havilland was blacklisted and didn’t work on a studio film for two years. In 1947, she won her first Oscar.

In 1949, she won her second.

Ms. de Havilland wrestled control away from these moguls and killed the Golden Age of Hollywood. In its place, a new age was born — this time, the power lied in the hands of he creatives and their agents, which led to the rise of superstars and their agents, like Lew Wasserman of MCA, Michael Ovitz of CAA, and Ari Emanuel of WME-IMG.

Today, it seems the Hollywood system is again at the end of its run. Can it survive? And should it?

Why Hollywood Is in Trouble

First… is there a problem?

I didn’t initially think to start here, but after reading quotes like this in CNBC [note]https://www.cnbc.com/2016/09/15/netflix-and-kill-is-streaming-hurting-movie-theaters.html[/note] from Tim Richards in CEO of movie theater chain Vue Cinemas (based out of the U.K.), it’s worth revisiting the premise:

“We’re having a record-breaking year this year. 2014 was a disappointing year globally, and the studios just didn’t get it right and that happens. It happens typically every five or six years.”

“Everybody predicted the ultimate demise of the industry, the Netflix approach, and everything else. (But) it was bad movies, and 2015 came back, rebounded, record-breaking year in almost every market in the world.”

I think this is wishful thinking on Mr. Richards’s part. Let’s look at why today’s Hollywood studio machine and their product is in trouble:

1. Ticket sales are sideways.

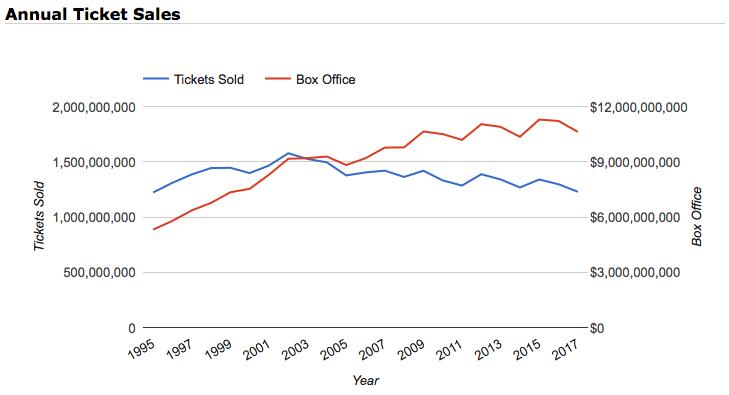

While box office revenue is expected to grow 2% in 2017, this can be misleading. More people aren’t going to the theaters, rather, ticket prices have gone up. In 2016, there were just under 1.3B tickets sold. 2017 will match this number. In 2006, 1.4B tickets were sold as reported by the MPAA (graph from The Numbers).

Plus, there’s an increased concentration of ticket sales, healthy box office numbers are consolidated to only a couple of films. The 80/20 effect plays a hand here — or in this case, 90/10 — 90 percent of the box office revenue comes from 10% of the films

2. Studio profits are down.

Overall profits for the big-five Hollywood studios — 20th Century Fox, Warner Bros., Paramount Pictures, Universal Pictures, and Disney — fell by 40 percent, according to Vanity Fair. [note] https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2017/01/why-hollywood-as-we-know-it-is-already-over[/note] In 2016, profits were down 14.6%, for a total of $4.18B (Disney making up for about 60% of that, according to the LA Times). [note]http://www.latimes.com/business/hollywood/la-fi-ct-cinema-pain-20161213-story.html[/note]

3. Hollywood is making too many sequels

Hollywood studios making a bunch of sequels is a sign that business is bad.

There’s an important distinction here: The Hollywood studio business isn’t bad because they’re making a lot of sequels. Rather: Business is bad, and therefore Hollywood studios have to make sequels (correlation, not causation).

From the studio’s perspective, producing sequels is sound business. There’s a built-in audience, — the people who saw the first film — and that makes the sequel a safer bet. Mathematicians call “an exploit.”

However, as studios spend more time and money exploiting films of the past, they’re not investing in the franchises of tomorrow. This behavior indicates a future so uncertain, the best (financial) play is to squeeze as much money from existing IP today.

Other signals Hollywood is in trouble

Alone, the following are worrisome. Collectively, it’s a big red bullseye on the back:

MoviePass discounts movies. The subscription service cut their price from $30 to $10 monthly. Ramit Sethi called this The Gap effect — when you’re constantly discounting your wares at 40% off, you’re in trouble.

DreamWorks Animation sold to Comcast for $3.8b. This is the studio that brought us Shrek, Madagascar, and Kung Fu Panda. It’s not a great price point for that kind of intellectual property. To put the dollar value in perspective, Facebook bought Instagram for $1b, when it made $0 revenue and had 13 employees. Facebook also paid $19b for Whatsapp, a messenger app.

Paramount studio valued at $8b. This is $2b less [note]https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2016/10/is-paramount-unsalvageable[/note] than what Sumner Redstone paid when he purchased it — 22 years earlier.

Continued diversification of Hollywood Agencies. Agency powerhouses CAA and WME started in the representation business. Today, representing interests of creatives is only a slice of what they do. Richard Lovett pushed CAA into sports in 2006, and with an investment of TPG Capital in 2010, they’ve continued to expand their interests. Today, private equity firm Silver Lake has a 51% stake in WME. WME merged with sports management company IMG to form WME-IMG. They also acquired an esports business, the Miss Universe Organization, and the Ultimate Fighting Championship.

The myths about why the Hollywood movie industry is in trouble

How did we end up here?

We’ll look at that. First, it’s not what most people think:

Myth 1: Shitty sequels and superhero movies are ruining Hollywood

As Nick Allen eloquently put it, “Audiences will be given a sixth helping of X-Men plus Fast and Furious 6, Die Hard 5, Scary Movie 5 and Paranormal Activity 5. There will also be Iron Man 3, The Hangover 3, and second outings for The Muppets, The Smurfs, GI Joe and Bad Santa.”

There are more sequels and superhero movies than ever. But are they shitty?

In 2017, 9 out of the 10 top domestic gross films in 2017 were based on existing IP (the outlier was Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk). Eight of the 10 films are certified fresh, and Despicable Me scored the lowest with 61%. Here is the breakdown [note]http://www.boxofficemojo.com/yearly/chart/?yr=2017[/note] as of this writing:

- Beauty and the Beast – 71%

- Wonder Woman – 92%

- Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 – 82%

- Spider-Man: Homecoming – 92%

- It – 85%

- Despicable Me 3 – 61%

- Logan – 93%

- The Fate of the Furious – 66

- Dunkirk – 93%

- The LEGO Batman Movie – 91%

Myth 2: Rotten Tomatoes is the destruction of the movie business

At the Sun Valley Film Festival, Brett Ratner (director of Rush Hour) bemoaned the review aggregator site, calling it “the worst thing we have in today’s movie culture. I think it’s the destruction of our business.” His company co-financed Batman vs. Superman: Dawn of Justice, which grossed $900 million worldwide, but fell short of expectations.

“I think it put a cloud over a movie that was incredibly successful,” Mr. Ratner said.

Aggregated review “scores” have changed the landscape of Hollywood and film, but the same could be said for Yelp and the restaurant industry, or Tripadvisor and hotels. An aggregated consensus of 27% (what Batman vs. Superman scored) is a signal of a poor movie, and most people don’t want to see poor movies.

Rotten Tomatoes is a megaphone, an amplification of quality, not what makes or breaks a film (the fact Batman vs. Superman grossed $900 million despite its Rotten Tomatoes score proves this point.)

Director Martin Scorsese also recently came out against the site, saying it ruins creativity. But as Tyler Coates of Esquire points out Mr. Scorsese’s argument “falters here. You can look at the Rotten Tomatoes scores of his last two movies as proof of that. The Wolf of Wall Street earned a 77% rating in 2013, and last year’s Silence earned an 84%. The former, however, vastly over-performed at the box office, making $91.4 million as opposed to the latter’s $7.1 million.”

Myth 3: Hollywood executives are stupid and/or have no taste

First, it’s a long uphill battle to become a studio executive. Many started in the trenches — in the mailroom at William Morris Agency, answering phones from 8am to 8pm, and reading scripts late into the night, until the words blur on the page.

You don’t get to a studio executive position being stupid. Or lazy.

However, at the end of the day, a studio is a business, and businesses exist to make money. So when it’s time for the P&L (profit and loss statement) executives are under no illusion: Their job is to make numbers, not art. (And if you can’t do it, there are a dozen hungry creative executives champing at the bit, ready to prove they can.)

There’s an expression in the software industry: “Nobody’s been fired for hiring IBM.” Make the safe bet and you get to keep your job. In the Hollywood film business, there are a number of ways studio executives can “hire IBM” (we’ll touch on each of these more in-depth below):

- Produce a sequel

- Produce based on existing intellectual property

- Hire the hot new lead to star

- Spend 50% or more on your production budget on marketing

And guess what? Sometimes it works. For example, Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales, despite poor press and worse reviews, still cleared just shy of $800 million globally. With a production budget of $230 million, it’s hard to call that a failure.

If it didn’t? The executive who greenlit the movie has deniability. Big name star? Check. Franchise? Check. $100 million marketing budget? Check check.

This is not asinine or stupid. It’s human nature. When the livelihood of you and your family is at stake, you make the decision you can justify after-the-fact.

The Real Reasons Why Hollywood is in Trouble

Navigating the real reasons why Hollywood is in trouble is like trying to hack through gnarly terrain with a nail file. Not helping matters is what’s at stake. To some, like Mr. Scorsese, an entire art form you’ve dedicated your life to is at stake.

For others, their livelihood is at stake. Not just Hollywood executives, but the two million people [note]https://www.mpaa.org/jobs-economy/[/note] employed and protected by the industry: the grips, the keys, the ADs, craft services. Everyday people rely on the Hollywood industry to put gas in the car, food on the table, and kids in school.

It’s worth taking the time to cut through the brush. Only by getting at the root causes, can we get to real solutions. Here are the three major reasons why Hollywood is in trouble today:

Reason 1: 50 Percent of Studio Profits Disappeared

And it’s not going back. At least according to Peter Chernin, chairman of The Chernin Group[note]*Sleepless in Hollywood* by Lynda Obst[/note]:

“The historical studio business, if you put all the studios together, runs at about a ten percent profit margin. For every billion dollars in revenue, they make a hundred million dollars in profits.

“The DVD business represented 50% of their profits. The decline of that business means their entire profit could come down between forty and fifty percent for new movies.”

So a huge chunk of the profit is disappearing. Where are (can?) studios recover this revenue?

If a studio’s got a big budget film, a franchise movie, perhaps one that revolves around an amicable cast of superheroes and rotating storylines and villains, you get two shots at making up some of that lost revenue.

That first shot is through ancillary revenue sources. Think: merchandising (toys, keychains, collectibles, Legos, PoP! dolls), TV spin-offs (Avengers, Agent Carter, New Mutants), video games (Lego Batman, DC Legends, Pirates of the Caribbean: Tides of War), amusement park rides and Graphic novels

The second shot is by making your big budget movie SO big, seeing the movie becomes a bigger experience than just seeing a movie. It’s an event, an experience that warps the mind and delights the senses with (specs, dolby speakers, 3D, or iMax). By transforming what was once a simple theatrical flick into an event, you’ll not only sell more tickets, but you can also sell tickets at a higher price point (after all, those speakers and widgets won’t pay for themselves).

(What about those non-big budget, superhero films? They suffer a triple-whammy: Not only are they losing out on those DVD sales, but they’re not going to recover that profit via ancillary revenue sources or charging premium prices for a premium experience (would you pay a $8 premium for Moonlight on iMax? Or pay $15 for a Baby Driver action figurine?))

As I pointed out earlier, the logic behind the big budget movie is sound. But it’s not enough. You can hike up ticket prices, and strike all sorts of licensing deals, but for that to pay off, people have to go to the movies.

Reason 2: Movies vs. the Kardashians

Unfortunately, that’s happening less and less. According to PostTrak,[note]http://www.businessinsider.com/movie-theater-attendance-is-declining-as-cord-cutting-becomes-more-popular-2016-9[/note] from 2014 to 2015, the number of people who would show up to theatres and decide what to watch on-site decreased from 32% to 28%. Going to a movie theater on a weekend evening is becoming a smaller and smaller part of our culture. Meanwhile, in 2015, the top films in theaters were illegally downloaded more than half a billion times.[note]https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2017/01/why-hollywood-as-we-know-it-is-already-over[/note]

In other words, theaters are engaged on two battlefronts: A product battle (movies vs. every other form of entertainment) and a distribution battle (when we DO watch movies, how we watch those movies).

The distribution battle is simply one of convenience.

- Convenience is king

- On-demand is everything

- So much so that even “the event experience” could make it worth it, and even then, often convenience still wins out

Now, the product battle: I don’t need movies for my entertainment anymore. I have countless forms of entertainment, that I can access 24/7 on a variety of form factors (phone, tablet, desktop, television). For the sake of exploring this topic, let’s focus on the narrative form of storytelling that happens across all these screens (and ignore all substitutes to seeing a movie, like video games, live events, Broadway, MMA fights, etc.).

Movies still have to compete with the one-two punch of the golden age of premium television plus Keeping Up with the Kardashians. They’re competing with 300 hours of Youtube uploaded… every minute. Tens of thousands of movies on Netflix, Amazon, Hulu. And in today’s world, we grow up believing we are the star of our own movie, so they’re also competing with platforms like Instagram, Snapchat, Twitch, Periscope, musical.ly, podcasts, Anchor, and dozens of others incubating as we speak.

There are 2 camps of thought to this disruption: Those who think this is a no-brainer. And those who can’t fathom a cultural institution like the cinema could be disrupted by apps built for sexting, filters, and the Kardashians.

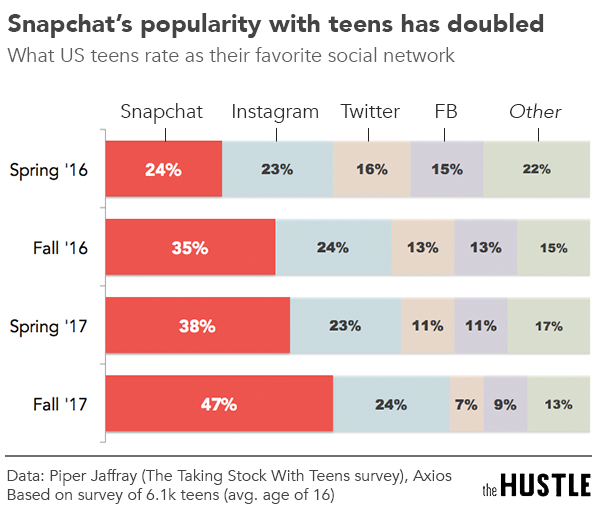

But according to Piper Jaffey, [note]http://www.piperjaffray.com/2col.aspx?[/note] Snapchat is the preferred social media platform for 47% of teens using the platform – up 12% year-over-year (image from The Hustle):

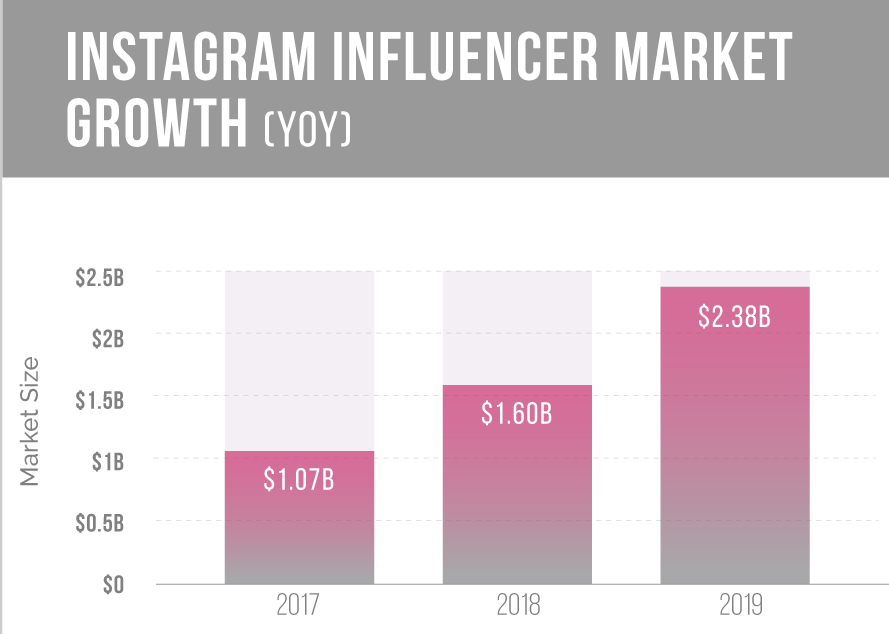

In April 2017, Instagram had 700 million MAU, or monthly active users. To put this in perspective, it’s only exceeded[note]https://techcrunch.com/2017/06/27/facebook-2-billion-users/[/note] by Facebook (2 billion MAU), YouTube (1.5 billion MAU) and WeChat (889 million). With it’s 700 million users, Instagram’s influencer marketing exploded to a $1B industry. By 2019, it’s estimated to double (graph from MediaKix).

Meanwhile, Keeping Up with the Kardashians is entering its 14th season, and a host of Kardashian apps are available to download on the iTunes store. One of those apps, Kim Kardashian: Hollywood, earned $74 million in 2014, according to Fortune[note]http://fortune.com/2015/09/22/kardashian-kyle-app-downloads/[/note], which is about the production budget for films like Despicable Me 2, Independence Day, and Wanted.

Unfortunately, in the face of this disruption, the film industry hasn’t gotten more innovative selling moves as Steve Jobs prophesied (“interesting, more precise, cheaper, efficient”). In fact, as the situation gets more dire, it becomes more apparent the industry possesses a limited vocabulary to respond:

- Produce big budget, event-worthy films with potential for ancillary revenue (as discussed above)

- Increase marketing spend

As you’ll see, the latter has become an arms race to the bottom.

Reason #3: Skyrocketing costs of marketing Hollywood films

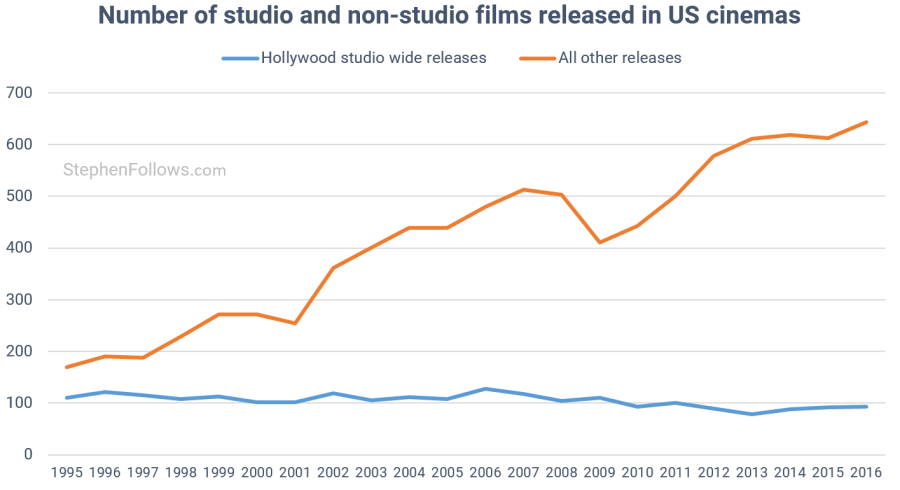

The resources allocated to the big budget films of today mean there’s less money to invest in smaller films. In other words, studios have defaulted to a strategy of taking bigger swings… but getting fewer at bats (graphs from Steven Follows):

The success of their big swings determines future movie slates, their production budgets, and who gets to keep their job. In other words, there’s enormous pressure for these big pictures to open, or hit projected numbers on opening weekend. But in a world with so many entertainment options to choose from, studios have to do everything in their power to pull viewers into theaters. That means pouring a disproportionate, irrational amount of money into marketing.

What kind of spend are we talking about?

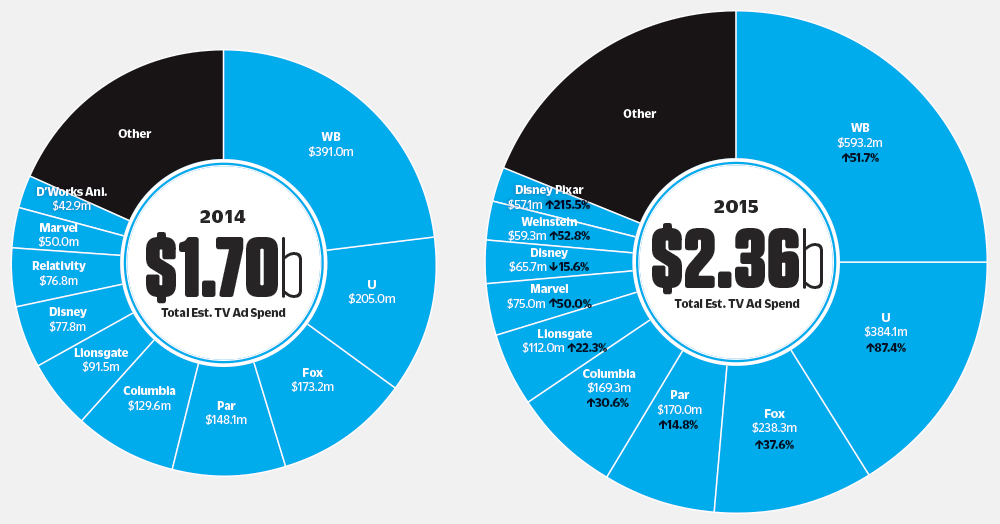

In 2014, marketing budgets hovered around $200m per studio picture.[note]http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/200-million-rising-hollywood-struggles-721818[/note] In 2015, 67 movie marketers placed 934 different spots more than 524,000 times on U.S. national television, for a total media value of $2.36b.[note]http://variety.com/2016/film/features/movie-marketing-advertising-tv-campaigns-1201724468/)[/note]

The problem with this kind of ad spend is it’s a vicious cycle, in success OR failure. If the film opens, the marketing spend on the movie sets a new benchmark on how much marketing future films require. If the film bombs, it’s marketing’s fault (or millennials, or Rotten Tomatoes). Either way, the studio takes a loss. Which puts more pressure on the next film, so they increase the marketing spend… and the cycle continues.

How can Hollywood studios save themselves?

Not an easy question. I’ll take a crack at it, but first, we need to look at the full funnel of the Hollywood system. The funnel should be simple enough to understand yet granular enough to see how pulling levers affect costs and revenue. Then, we can hypothesize what happens when different levers are pulled, prioritized, and optimized.

I call this the Reverse Hollywood funnel. In a traditional marketing funnel, a large number of people are acquired at the top of the funnel but only a small percentage converted at the bottom of the funnel. The Reverse Hollywood funnel is, well, the reverse: a small number of people involved in the project at the start to convert a large number at the bottom. Also, costs increase as we move down the Reverse Hollywood funnel:

Costs of Acquiring IP < Talent Agreements < Product < Marketing

Here’s how I’d model the funnel. The sequence isn’t perfect, as certain events may occur concurrently or in a different order. Again, this is simplified and not to be taken as the Gospel.

- Acquiring the Intellectual Property – The underlying intellectual property (script, book, graphic novel, life rights, board game, video game, etc.) is bought and sold.

- Development – The script is written (and rewritten) and submitted to the studio. The studio sends notes back to the writer for another rewrite. The number of times the studio can ask for rewrites is formalized in their contact with the writer. The writer incorporates those notes into the script.

- Attaching elements – Talent (actors, the director) get attached to the film. In other words, should the studio greenlight the film, the talent agrees to participate for a set price, known as their quote. For A-list talent, part of that quote can include a producing fee and separate deals for their producing partners.

- Pre-production, Production, and Post – All the work of putting the film together. Scouting locations, casting, shooting, editing, scoring, and everything in between.

- Product strategy – Determining all avenues of revenue for the film. Includes but is not exclusive to pre-selling to foreign markets, striking brand partnerships for product placement opportunities, and ancillary revenue deals (books, toys, apps, soundtrack).

- Marketing – Encouraging, enticing, and cajoling people via traditional and digital channels to pay $16 to come and watch the film.

- Distribution – Everything to do with the film’s release: When will they release it? What markets will they show the movie? What’s the roll-out strategy look like? How many theaters?

Three Optimizations to the Reverse Hollywood Funnel

Now that we’ve sketched the Reverse Hollywood Funnel, we can hunt for optimizations within the funnel.

The further down into the funnel we work, the more impact we’ll have, since more resources are used, and more people affected. On the flipside, the further down we go, the more friction we’ll encounter, trying to change the status quo.

For example, here’s an admittedly simplified way to cut down on costs: Pay less for the intellectual property. Instead of paying an option/extension/purchase price of $350,000/$350,000/$2.25m for a single book, pay $200,000/$200,000/$1.12m. That’s about $1.5m saved on intellectual property alone.

The problem is that $1.5m saved is a drop in the ocean compared to the rest of the cost of turning that book into a film.

The same applies to looking to cut costs when attaching your stars. Even if you lower two star actor salaries from $15m to $12m for a total savings of $6m, it’s only a 6% savings on a $100m production, that requires another $50m to market. Not insignificant, but not a huge needle mover, either.

Plus, if the studio cuts the upfront salary, they have to make it up on the backend in the form of profit participation, so money saved today cuts into potential upside tomorrow.

That’s the balancing act we have to strike when considering optimization options: the impact of the change versus the friction created by change.

I’ll touch on the three areas of optimization I believe can move the needle. None are quick-fixes, but getting even one of these right can dramatically change the Hollywood machine

Optimization 1 – Double-down on Emerging Markets and Brand Partnerships

Unless your protagonists are wearing spandex or are capable of manipulating the Force, ancillary revenue streams (merch, soundtrack, graphic novels, etc.) won’t make much of a dent. The real needle movers under the Product Strategy umbrella are Emerging Markets and Brand Partnerships.

Emerging Markets

Hollywood studios could take a few pages out of Facebook’s playbook.

In 2007, it seemed Facebook had peaked at 70m users. Mark Zuckerberg put executive Chamath Palihapitiya in charge of revamping growth, and Mr. Palihapitiya looked internationally to expand their user base, but discarded the playbook on how it was done in the past.

Most companies took a top-down approach to translating sites: Start with widely used languages that were easily translated from English (Spanish, French, German) and work your way down. Mr. Palihapitiya eschewed this for a bottoms-up approach — they built software so users could translate Facebook themselves.

The army of volunteer translators captured the nuance of culture and language better than professional translators, and by 2008, Facebook reached 100m users.

Later, they noticed new users had low-end devices with really bad connectivity. Accessing bandwidth heavy sites like Facebook was too expensive. So the company M&A’ed their way to Facebook Lite, a stripped down version of Facebook, which was critical to reaching 200m users in emerging countries (Vietnam, Bangladesh, Nigeria).

How does Mr. Zuckerberg plan to capture future emerging markets, without Facebook or phones or even Internet connectivity? Bring the Internet to them[note]https://www.wired.com/2016/01/facebook-zuckerberg-internet-org/[/note], of course.

How does this apply to Hollywood? That the foreign market — especially China — is a huge revenue driver (70% in 2015) for the studios is no big surprise. However, there are restrictions: the Chinese quota system that only allows 34 overseas films each year. Pirating. Censorship. To survive, the studios need to mix up their playbook as well.

Hollywood needs to play by these rules, while finding ways to expand the depth of its reach in markets where they already have a toehold, like China. They could mine better data as to what films performed well in China and create “local” films, that are shot and produced in China (getting around the quota). With that same data, they could tap into the studio library and find films that’d play well to Chinese sensibilities and license them to distributors, both online and on television. Films could bake in characters or plotlines that’d allow for a backdoor pilot of a Chinese-exclusive television show.

Studios also need to expand their breadth to future markets that won’t have access to the cineplexes and iMax screens. Instead of going bigger, how can they go smaller? How can they cater to the markets that are 10-years away from being a buying powerhouse? In other words, studios should start thinking about how to “bring the Internet to them” today, so they’re in position to profit tomorrow.

Brand partnerships

Studios can’t make up the margin on ancillary sources. The film itself, like Orwell’s Boxer, must commit to the mantra, “I will work harder.” Higher ticket prices and selling the film to foreign markets are two ways it can do that. The third is brand partnerships.

Brand partnerships, or product placement, date back to the age of silent films. If studios are going to survive, we’re going to see a lot more of these: More ET’s gobbling up Reese’s pieces, James Bond drinking Heineken instead of his signature martini in Skyfall, and the long car advertisement that is the Transformers franchise.

We’re going to see more of all of this, perhaps even entire movies built around promoting a product, a la The Italian Job, which turned a 90-minute car ad into a decent heist film. The Italian Job proves that product placement can be fluid and make sense to a story, as long as it’s baked into the creative process from the get, and not painfully tacked on by marketing executives at the eleventh hour, i.e, A.I., starring Will Smith.

Optimization 2 – Change the Movie Marketing Mix

Here’s the last full commercial I watched (it’s worth the 2 minutes 30 seconds, I promise):

That was 2 years ago.

What’s an American Family Insurance commercial got to do with Hollywood movie marketing?

Traditionally, studios budget 50% of their production spend for marketing. So if a movie cost $100 million to make, it’ll cost $50 million to sell. Yet despite the fact we live in a world where people don’t watch commercials, that’s where most of the ad spend goes.

The population who consumes “live” television is getting smaller. Save for live sports, more people are DVR’ing their shows and watching it on our time. When we do this, we’re fast forwarding right through the ad spot some media buyer blew half their budget on, in the hopes that a last minute buy on prime-time would help the movie open. (Or, if we are watching live television, the moment the programming switches to commercial, we’re reaching for our phones and ignoring the TV.)

To compound the problem, media buyers have no leverage to negotiate on their television ad buys. Studios are locked into a specific window to buy their time: 3- to 4- weeks before the film opens. There’s no room to negotiate. So the ROI is never there.

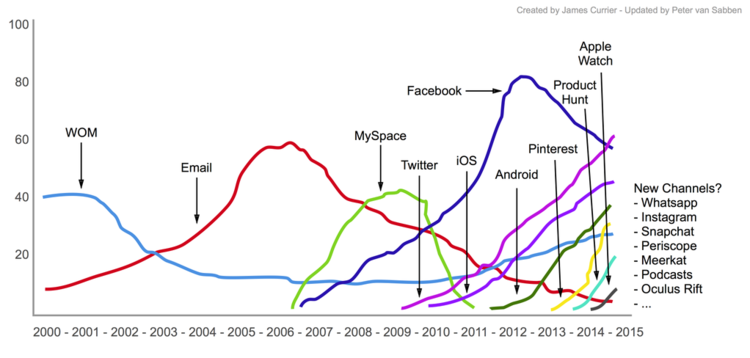

This is not a critique on television or commercials. I’m not saying either are dead, just that that’s the state of the union for this marketing channel. As James Currier of NFX shows in the chart below (updated by Peter van Sabben), channels evolve. There’s an ebb and flow. Overtime, new channels get added to the mix (e.g. Alexa skills, musical.ly, Anchor.fm).

So if the ROI isn’t in television ads, where should studios reallocate those marketing dollars?

There’s no magic bullet. Studios have to do the hard work of testing all the channels that have emerged in the last 10 years and figure out what moves the needle. They have to test Facebook ads, Snapchat geofilters, sponsored Twitter moments, Instagram influencers, Reddit AMAs. (By the way, Facebook ads might feel “new” compared to traditional marketing, but it’s hardly an emerging channel. Last quarter Facebook had $9.2 billion in ad revenue, which was an increase of 47% over the year prior.[note]https://stratechery.com/2017/trustworthy-networking/[/note])

Instead of wishing millennials would stop staring at their phones all day and spend money on a movie ticket, figure out what apps they’re using on their phones, and learn how to market there.

Most channels won’t perform. One or two will hit. It depends on the movie, the audience, and the talent behind your creative. Hunger Games: Catching Fire saw wild success with their in-person activations, their Cover Girl partnership, and mobile games. The same tactics probably wouldn’t have saved Baywatch or Jumanji. The movie and the target audience were completely different. So the marketing needs to be different, too.

How should a studio start testing these channels? In Reforge, an education company that teaches marketers from Facebook, Google, and Uber, we (I work there) think allocating resources to different channels as a series of bets.

Currently, studios put most of their bets squarely on Saturated channels. They want to keep some bets in saturated channels to maintain growth, but they have to shift resources to high risk, high reward channels (Golden Age and Emerging Channels) to capture new opportunities as growth continues to slow in saturated channels.

Some final thoughts on mixing up the marketing mix: None of this is to say studios should move all their money out of TV ads and traditional advertising. These channels have huge reach you can’t get anywhere else. It’s not that TV commercials don’t work. They just don’t work well for the price.

You can’t hire an intern who comes in twice a week and takes a lot of Snapchat selfies, and say you checked the box on investing in digital marketing. This is not a one-off project or magic bullet. No one’s going to run a single Instagram Influencer campaign and turn everything around. Not to pick on Baywatch or Jumanji, but both starred Dwayne Johnson, perhaps the most powerful Instagram Influencer out there. And neither movie opened. This is going to take time.

Studios got better at commercials because of years spent working at commercials, honing the creating, the programming, and the media buys. The same applies to digital — it takes time to figure out the best place to put the copy, the music, etc. Changing the marketing mix is an investment, but one that could save the industry.

Optimization 3. Focus on the experience

In September 2017, Toys R Us, the American big-box toy retailer filed for bankruptcy. They can blame the usual suspects (ecommerce, millennials) for bringing down the company, but it doesn’t explain why Child’s Play in Northwest Washington is thriving with 3% YoY growth.[note]https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/why-neighborhood-toy-stores-are-thriving-while-toys-r-us-goes-bankrupt/2017/09/22/2f1e2b54-9d48-11e7-9083-fbfddf6804c2_story.html[/note]

The difference is the experience. At Child’s Play, the toys are carefully curated and children can actually play. If you’ve been to a Toys R Us recently, it’s like shopping at Costco, but less fun. Howard Davidowitz, a retail consultant who worked with Toys R Us in the 1980s and 1990s, said:

“Toys R Us, which had basically devolved into a warehouse, did not have the vision or the money to give its customers a great experience. For a toy store to survive, they’ve got to create the kind of fun that Amazon can’t.”

Look at stores across America. Ones that ignored the shopping experience like Kmart and Sears are out of business, or on the way out. At the mall, “experiences” are replacing retailers: Lucky Strike, Dave N Buster, and “Mystery Rooms” instead of Baby Gap, H&M, and DSW.

To survive, studios and cinemas need to overhaul the movie-going experience as well. Adding high-priced tickets to IMAX and 3D options provided a buffer against flat ticket sales, but it’s not enough. Especially considering most studios treated 3D as a gimmick, converting films into 3D in post-production in an exploit-heavy move (Wrath of Titans, Texas Chainsaw 3D, Underworld: Awakening) and not a native component to the storytelling (Avatar, Edge of Tomorrow).

The industry is taking its first steps in this direction. Dreamscape Immersive plans to open its first VR Multiplex in Los Angeles in September 2018.[note]http://variety.com/2017/digital/news/dreamscape-immersive-vr-multiplex-1201986722/[/note] The spirit of the move is in the right direction: building experiences that can’t be replicated at home (yet), not just tacking on a gimmick in post-production. Personally, I don’t believe this goes far enough yet — for commercial viability, I think VR needs to deliver a 100x experience we can’t get with consumer headsets, and that’ll require body rigs, a la Ready Player One.

Time will tell how this plays out, but of all the recommendations, it’s the biggest and most ambitious way to save Hollywood studios. If studios do move in this direction, I could see studios implementing a barbell strategy in their development slate: Producing one or two of these expensive, immersive VR experiences and hoping for home runs, while balancing it out with a dozen low-budget singles — movies produced for under $10m and marketed for less than $5m. Diversification will be solved with extremes, not averages, and the middle ($70m – $40m productions) will get squeezed out.

Conclusion

Months ago, I saw the first narrative move, a 12-minute film called The Great Train Robbery. The film was grainy, silent, and unevenly paced. I was so enthralled, I watched it twice.

The Great Train Robbery first opened In 1903, and people went in droves to their local nickelodeon to pay their 5 cents and watch. The Hollywood machine gave them an experience they never encountered before. It was magic.

Today, there’s no shortage of great storytellers. The Hollywood system will continue to produce hit films, even if immersive VR never comes to fruition or studios never replace the profits lost from DVD sales. Technology and time crippled the music industry, but it’s still possible for a star to produce a record-breaking, hit album — just ask Taylor Swift[note]https://www.usatoday.com/story/life/music/2017/11/03/taylor-swifts-new-album-reputation-sells-record-breaking-400-000-pre-orders/829527001/[/note]. But these stars and hits will be further and fewer in between, until Hollywood is a dimmer version of its former glamorous self.

###

Photo Credit: The Hollywood Reporter

2 Comments

Pingback: How Television Shows Get Made | Christopher Ming Blog

Pingback: How to Become a TV Writer in 2022