I’d been writing a screenplay and used Ryan’s book as a reference. Then I saw that David Siteman Garland had interviewed Ryan a while back and immediately downloaded the audio. The Rise to the Top Interview with Ryan Holiday covers Ryan’s book, TRUST ME, I’M LYING: CONFESSIONS OF A MEDIA MANIPULATOR (DSG’s affiliate link). I read the book when it first came out in July 2012) and watched Ryan speak at a signing at the Book Soup book store in West Hollywood.

This interview serves as an excellent primer for Ryan’s book, which covers the techniques of the media strategist who’s worked with Tucker Max and American Apparel. For example, they talk about “moving up the chain” and that a blogger’s value comes from hitting quotas set for them. The book is marketed as a “how-to” in manipulating the media and defending yourself from manipulation, which I feel is a bit of a misrepresentation. The tactical analysis of Ryan’s methodologies aren’t very indepth, and I found a great deal of the latter half redundant.

This interview serves as an excellent primer for Ryan’s book, which covers the techniques of the media strategist who’s worked with Tucker Max and American Apparel. For example, they talk about “moving up the chain” and that a blogger’s value comes from hitting quotas set for them. The book is marketed as a “how-to” in manipulating the media and defending yourself from manipulation, which I feel is a bit of a misrepresentation. The tactical analysis of Ryan’s methodologies aren’t very indepth, and I found a great deal of the latter half redundant.

Nor is the interview (or book) something I’d prescribe as a “must listen to” in the self-development track.

However, if you’re interested in understanding the mechanics of blogging and how it’s changed today’s media, this is a worthwhile interview (and the book, a worthwhile read).

Ryan and David also shared a handful of nuggets about his work, which I’ve included below.

*I don’t guarantee these are word for word quotes. Consider them more like very accurate paraphrasing. Italics are my notes, bold is mine.*

07:30 – RH “I’m a big proponent of the vertically integrated model, that you don’t make a product, ship it, and then decide how you’re going to sell it. For me, how can I put things in the book that are going to make people talk about it. How can I create a cover that’s going to create a spectacle and generate attention. How can I reach out to my contacts and get a base going and gather momentum. For me, I saw this book as an opportunity to prove the things in this book.”

The vertical integration model Ryan discusses below is what Seth Godin has been saying for years — marketing isn’t what Mad Men. Marketing is the product.

09:23 – RH “I saw Tucker was working with other writers and authors, and I thought, ‘I’m not old enough yet, but I want to do that someday. I want to be one of those people. I decided I was going to meet Tucker, work with him, and learn from him. So I waited until I had my chance… I wrote an article about him, knowing that Tucker liked to post articles about him that he liked… We started a relationship from there, and as a 18-19 year old kid, I sent him every question that popped into my head.”

Ryan’s message here is that he used a Charlie Hoehn method to connect to Tucker Max. Ryan had a strategy that took in account what he wanted and how he was going to get it. It’s an example that demonstrates if you want something, you can get it — you’ll have to be intelligent, strategic, and genuine, but you can get it. (I realize I may have the causation mixed up, as Ryan probably contacted Tucker Max before Charlie worked for Ramit, but I’ve always thought of this as the Charlie Hoehn method, as publicized in his Recession Proof Graduate and Tim Ferriss’ post, 12 Lessons Learned While Marketing ‘The 4-Hour Body.”)

RH – “Dov Charney of American Apparel saw that all the money Nike was saving by using these child workers in Indonesia was going to endorsements and Lebron James and the New York Times stores. And he thought this was an inefficient model. Dov decided he wanted to pay his workers a fair wage, but he wouldn’t use these kind of endorsements. So the question became, how do we market this global brand on what is essentially a shoestring marketing budget?”

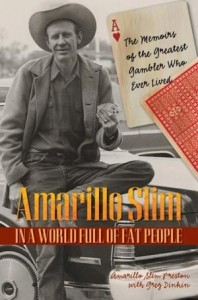

37:43 – DSG “The cover is badass.”

RH “I hate business book covers. I wanted an amazing book cover. The designer who did this is amazing. She did Tucker’s book covers, she read the book and loved it. She asked me if she could make the cover, and I told her ‘I would kill to have you do it.’”

The cover artist is Erin Tyler. She also designed many (most? all?) of the blogs on the now defunct Rudius Media websites. I interviewed her for a cover story on blogs-to-books when I was at Rutgers, and I remember her being very accessible and sweet. She used to blog at The Bunny Blog, and her design work can be found at Erin Tyler Design.

Photos Credit: timferriss