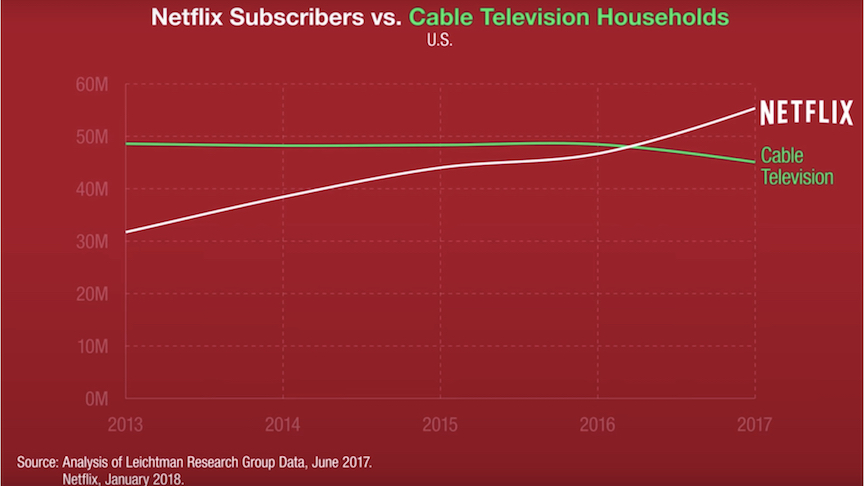

Cable television, we had a good run.

The “Third Golden Age of Television” — the influx of creator-driven dramas on cable and premium channels — was spectacular. Men (it was mostly men) changed the television landscape with shows like The Wire, The Shield, The Sopranos, Mad Men, Breaking Bad, and Game Of Thrones. These were some of the best TV series to watch.

Photo Credit: Spin

Photo Credit: Spin

But this golden age of television is over. From its ashes rises a new dynasty, one that’s less concerned about creator-driven content, and more about data and distribution.

Cable television’s loss of market share and the end of the “Third Golden Age of Television” was a strategic blunder, not a creative one.

Cable optimized for quality content and draw audiences and ad-revenue dollars. Streaming services optimized for data and distribution to draw audiences and subscription dollars. Data and distribution are the linchpins for survival in this landscape, not content alone.

John Landgraf called it

Artist-friendly network heads, like John Landgraf, CEO of FX Network, made personal commitments to creator-driven shows. “The business should support the artist,” he said in an interview with Andy Greenwald[note]Hollywood Prospectus Podcast: FX President John Landgraf | https://goo.gl/cEspjp[/note].

He greenlit Louie and gave Louis CK full control. Under his watch emerged shows like Archer, It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, Justified, The Americans, and Fargo, to name a few.

But Mr. Landgraf was also a visionary when it came to where the television game was headed. Sensing its demise in 2016, he said at the Television Critics Association press tour in 2016[note]FX’s John Landgraf Sounds Alarmed About Potential Netflix ‘Monopoly,’ Overall Series Growth | https://goo.gl/cGxxAN[/note]:

But Mr. Landgraf was also a visionary when it came to where the television game was headed. Sensing its demise in 2016, he said at the Television Critics Association press tour in 2016[note]FX’s John Landgraf Sounds Alarmed About Potential Netflix ‘Monopoly,’ Overall Series Growth | https://goo.gl/cGxxAN[/note]:

“I just think that’s something that we as a society should be paying attention to in general. I think it would be bad for storytellers in general if one company was able to seize a 40-50-60% share in storytelling. I don’t think monopoly market shares are good for society, and I think they’d be particularly bad for society and storytellers if they were achieved in the storytelling genre.”

It was a thinly-veiled warning about Netflix’s growing dominance. The warning was too little, too late.

What killed cable television?

In one staff meeting at the literary management company where I used to work, we were discussing where to pitch a writer’s pilot.

“How about Netflix or Amazon?” someone joked. The room laughed.

The irony strikes with the force of a battering ram now, but look at it from our perspective: the networks, studios, and production companies have been in the television game for decades.

The executives? Same. They were the tastemakers. They knew story. Most importantly, they had the relationships with the talent, the directors, writers, and actors needed to make a show. How could Netflix (known for streaming and slanging DVDs) and Amazon (known for 2-day shipping) compete?

In a strictly content-driven game, they couldn’t.

So they changed the game.

How Netflix changed the game

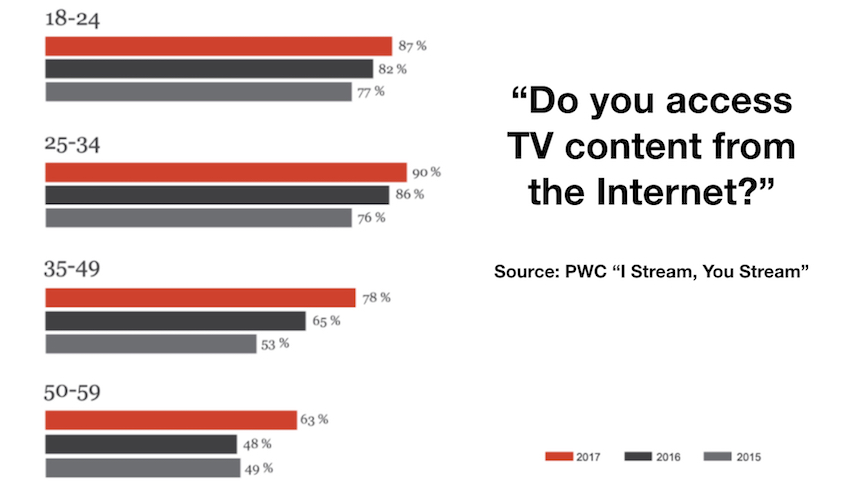

Across every age demographic in the United States, more people are streaming content and watching less live or scheduled programming.

- Ages 18-24: 87%

- Ages 25-34: 90%

- Ages 35-49: 78%

- Ages 50-59: 63%[note] PWC “I Stream, You Stream” | https://goo.gl/GopGCk[/note]

Netflix sounded the trumpets and led that charge. Here’s a (simplified) look at how it happened:

- Netflix created a better user experience around DVDs

- Later, they expanded their offer studios and networks: “We’ll handle the distribution of your shows and pay you a licensing fee. You focus on content, and we’ll take care of all the techno mumbo jumbo”

- Netflix offered streaming content to consumers at a competitive price and eschewed an ad-based model

- Consumer behavior begins shifting to streaming. Cord cutting begins

- Networks start to wise up and realize Netflix controls data and distribution. They beg for data. Netflix says “nah”

- Networks begin launching their own streaming services and letting licensing deals expire

- Netflix decides to get into the content game

- In 2018, Netflix plans to release 80 movies, according to CCO Ted Sarandos. That’s more than most major film studios – combined[note]Quartz: Netflix will release more movies in 2018 than most major film studios combined | https://goo.gl/txQ39x[/note]

Credit: L2 Inc | Winners and Losers, Disney Prepares for War

Credit: L2 Inc | Winners and Losers, Disney Prepares for War

Hollywood television executives were right: in a battle of content, Netflix didn’t have the resources to stage a coup. That’s why, like seasoned Mongol cavalry, they shifted the battlefield to areas where they possessed the advantage: in data and distribution. With these defensive moats in place, they started making inroads on content.

It’s unlikely Hollywood network executives will be able to cross that moat. The problem isn’t talent or technology, but incentive. Networks operate on an ad-based model — they generate revenue based on how many people watch the commercials in between the scheduled programming.

This provides the revenue the executives need to appease stockholders and (more importantly to them) keep their jobs. However, this dependency only widens the moat between the networks and their streaming competitors.

Data and distribution is king, not content

It doesn’t matter how good a show is if you can’t watch it.

During my time working with Dennis Lehane, we published two books (World Gone By and The Drop). One movie was released (The Drop) and another went into production (Live By Night).

But what we wanted more than anything was a greenlit television show. We got close but it didn’t happen during my tenure.

So when Dennis started working on Mr. Mercedes, a television show based on Stephen King’s book, I was ecstatic. I couldn’t wait to watch it.

The show’s been out for six months, and I still haven’t watched a single episode. That’s because it’s only available on AT&T’s Audience Network, and I’m not a subscriber. I don’t even know how to become a subscriber.

Peter Thiel had this great insight about products and it applies equally as well to Hollywood products as it does to tech products:

“Poor distribution — not product — is the number one cause of failure.”

– Peter Thiel

It doesn’t matter how good the show is if raving fans can’t watch it and tell their friends they need to watch it. Even a small, rabid audience can bring a show back to life (e.g. Veronica Mars, Community) but you need an audience. Without one, the show will run out of legs.

It’s not just networks that get this wrong. Even tech-giant Apple didn’t crack the formula in their first foray into original programming. I was one of the seeming handful of people who WANTED to watch Planet of the Apps. I subscribed to Apple Music just to subscribe to the show and be able to stream it to my computer or phone.

Yet for the life of me, I couldn’t figure out WHEN Apple released a new episode OR how to download it to watch it. After a few attempts, I unsubscribed.

There’s been a lot of fanfare about Apples $1 billion investment into content. In a move comparable to Netflix’s House of Cards, they ordered two seasons (20 episodes) of a straight-to-series show based on Brian Stelter’s Top of the Morning, starring Jennifer Aniston and Reese Witherspoon. The difference is Netflix had distribution, data on binge-watching content, and could deliver a seamless watching experience, all the elements needed to turn a television show into a cultural zeitgeist.

Or to put it another way: Apple couldn’t deliver a show I signed up to watch. Netflix can personalize a show’s album cover to make me more likely to click.

Where does the Mouse fit in with all of this?

There are a few reasons why if there’s one studio who can close the gap on Netflix’s data and distribution lead, it’s Disney:

Disney’s brand moat

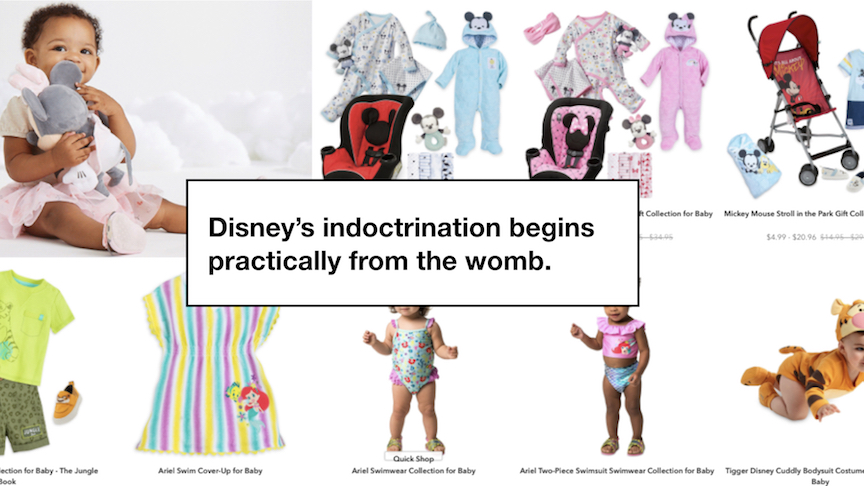

No brand is more capable of indoctrination. It starts practically from the womb.

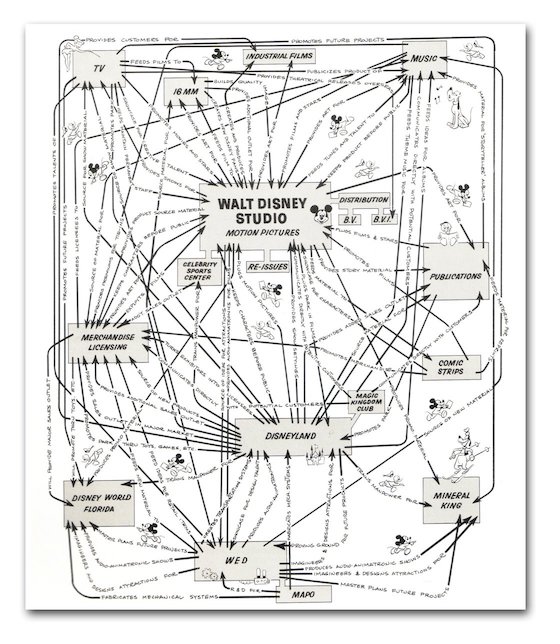

As we see from a visual map of Disney’s strategy, there are hundreds of touchpoints from the womb to continue beating the Mouse’s war drum, from Elton John songs to amusement park rides to children books to Christmas ornaments.

Disney saw the writing on the wall

Executives decided to exercise their option to remove Disney movies from Netflix, starting in 2019, and will launch their own streaming platform, along with an ESPN streaming service.[note]https://www.cnbc.com/2017/08/08/disney-will-pull-its-movies-from-netflix-and-start-its-own-streaming-services.html[/note]

Disney’s Fox acquisition

Disney will acquire many of 21st Century Fox’s assets. That includes the studio, TV production company, and cable channels (certain assets are excluded, like their news business). In 2017, Disney and 21st Century Fox accounted for 34% of ALL theatrical revenue.

The dark horses

This landscape is constantly changing, and there are plenty of players who are one disruption or innovation away from unseating Netflix as the leader of the pack. We still spend an incredible amount of our time on Youtube — 3.25 billion total hours watched… in a month.[note]37 Mind Blowing YouTube Facts, Figures and Statistics – 2018 | https://goo.gl/eXHefo[/note] Amazon invested $1 billion dollars into a Lord of the Rings television franchise.[note]Amazon’s $1bn bet on Lord of the Rings shows scale of its TV ambition | https://goo.gl/WF2CdQ[/note]

At the time of this writing, Facebook and Snap are facing a great deal of backlash (the former around privacy and data issues, the latter around poorly received user experience updates) but it’s too early to say if this is the beginning of the end. For what it’s worth, I still don’t think it is.

Finally, the battle for net neutrality could also play a pivotal role in this saga. If we lose net neutrality, and Internet providers decide to throttle back service to any of these streaming services, it would severely handicap any distribution advantage gained over the last decade.

###

Photo Credit: Sarah Reid

1 Comment

Pingback: How to Become a TV Writer in 2022