I’ve been thinking a lot about small failures lately.

In my experience, they’re more difficult to publicly face than large failures.

For example, in 2008, when my father opened the first Shogun, the idea that “this might might work” didn’t cross my mind too often. I felt like:

“Of course this might not work!”

It’s a big risk. The economy is depressed. One out of 4 restaurants fail in their first year. That number rises, to three in 5, over the next 3 years.

We faced plenty of other obstacles:

- Was there a market for Japanese food in Delmar?

- Was the market in the Capital Region over saturated?

- Lack of knowledge of this particular business.

There was an enormity to that task that made it okay if we didn’t succeed.

I followed the same logic with moving to Los Angeles and trying to start a career in Hollywood. There wasn’t much fear, because there were already so many challenges:

- Didn’t know anyone in Los Angeles

- Didn’t know anything about the entertainment industry

- No job, or apartment lined up to serve as a safety net

If things didn’t work, there was an enormity to the task that allowed me to shrug and say, “well, if it doesn’t work out, it doesn’t work out. Let’s give it a shot.”

I say this with no brag. This isn’t unique, people do it all the time with varying degrees of success.

The Topic of Failure and Fear

Where it manifests and how to manage it, gets covered ad nauseum in the self-development world. Three techniques worth mentioning are:

- Regret Minimization Framework (attributed to Jeff Bezos) – in 50 years, what decision would you regret, doing it or not doing it?

- Fear Setting (attributed to Tim Ferriss) – identify your fears, how to prevent, and what you’d do to recover.

- Understanding the Lizard Brain (attributed to Seth Godin) – fear is an artifact of our evolutionary response to life-threatening stimuli in our environment, that we continue to experience today (even though our lives aren’t actually in danger).

For endeavors or projects that’d result in a big failure, these techniques are especially helpful.

Fear On a Smaller Scale

On a smaller scale, however, it doesn’t work as well. Some examples:

- Making Youtube videos no one watches

- Starting blogs no one reads

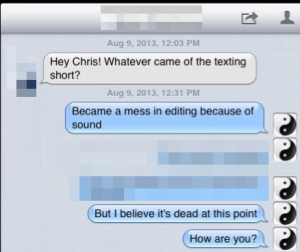

- Sending emails that don’t get responses

- Rejection

This has been exacerbated, I feel, in part because the idea in Hollywood is that any failure is completely unacceptable. That you’re not allowed to misstep, and “assumption is the mother of all fuck ups.” When you do fail, it’s so public:

- Hollywood is actually very small town like – everyone talks to everyone

- The iterative approach is not widely accepted

- They’re quick to criticize what hasn’t been done before

Which in turn, is further exacerbated by social media, where everyone naturally posts the good things in their life, and you begin to thinking everyone is doing better than you in their carefully crafted social presence. You begin to think you’ll be defined by this one failure.

So how do we overcome that?

What’s helped me is to find examples of others who faced public failure or criticism, and who have either addressed it, or moved on so quickly this was barely a blip on their radar. I make informal case studies of the “bigger names” out there, to grasp their mindset. Those are below:

Case Studies

Oprah and Arianna Huffington Ripped On in Deadline

In an article entitled DESPERATE: HuffPo and Oprah Team Up Now that barely passes for journalism, Nikki Finke reams out Oprah and Arianna Huffington for all of Hollywood to see. As Hollywood knows, Nikki never wears kid gloves, but in this article in particular, there’s an animosity that goes regular snark:

“This pathetic pairing sounds to me like an ill-conceived partnership, and it’s interesting that no mention is made of AOL which bought HuffPo last year.”

How does Oprah respond to Nikki? She doesn’t.

First she has a nervous breakdown.

Then she gets over it. And six months later, goes back to kicking ass.

Tucker Max versus Gawker

Tucker Max’s life has been fairly public. Posting stories and building a brand around all the women you’ve slept with and treated poorly will do that. He’s made the public very aware of his successes.

“I’m so far up the power law curve of book sales, dude,” Tucker told me. ”The very tip-top are J.K. Rowling and Stephen King, Stephanie Meyer, James Patterson, and Paulo Coelho. People who sell tens or hundreds of millions of books. That’s just a different game. That’s like, the Bible. They’re competing with the Bible. I’m not in the Bible tier.” (I can hear the religious among readers thinking: thank goodness!)

“I’m on the tier below that. But still, on the power curve, I’m all the way at the tip. I’m on the same tier as Tim Ferriss or Chelsea Handler or Jeanette Walls—we’re in the 2, 3, 4 million range.” — as told to Michael Ellsberg

Of course, this kind of publicity is a double-edged sword. For every success Tucker trumpeted, Gawker splashed his failures all over its front pages. It’s even created a special page on the site, breaking down this Tucker-Gawker feud to its individual campaigns.

Some of Tucker’s public failures:

- His movie, based on his best selling book, I HOPE THEY SERVE BEER IN HELL, bombed

- His media company, Rudius Media shut down in 2009

- During an interview on Sirius Radio’s The Opie & Anthony show , he was essentially laughed out of the room.

Yet amidst the waft of all this dirty laundry, Tucker has marched on. He’s moved beyond his fratire brand, started a new blog, published on the Huffington Post, and getting his rebirth featured in Fortune.

Love him, hate him, admire him or loathe him – he’s taken his brunt of public failures.

And he’s still standing.

Blogger / Entrepreneur Tynan and His narcissism

Blogger Tynan Smith and his lifestyle was recently featured (favorably) in the San Francisco Gate. What followed next, he describes in his blog post, was “hundreds of comments, 95% of them negative.”

“The negativity was absolutely astounding. I could hardly believe how many people spent the time to sign up and leave vitriolic comments.”

He could have ignored the article, and all the negative comments. He could have just called everyone haters. But Tynan didn’t. He addressed the fact many people felt he was a narcissist, and even owned up to it:

“I wear a silver necklace with my name on it.”

Then he went back to programming and writing. His work went on.

An Author’s Fans Vote “No”

Blogger and Science Fiction Author Jamie Todd recently put out a survey, asking his readers if they’d be interested in him putting out a newsletter. I don’t know how many readers/subscribers he has. But 50 people voted in this survey, and the response was overwhelming “no.”

Jamie could have swept this poll under the rug. He could have pretended like it never happened. Regardless of how stoic you are, that must take an emotional toll, your readers telling you, “no, we don’t want this.”

Instead, Jamie posts the results. He says, “thanks for voting. I appreciate the feedback.”

He gets back to work, posting nearly everyday, writing thousands of words a week, and continuing his Going Paperless Series.

Ramit Sethi covers “3 Crushing Fears I Had”

Best selling author and personal finance blogger Ramit Sethi covered these 3 fears to his email subscribers. They were:

- Charging for products on his site

- Firing people

- Saving money in strange places

He says:

“I looked around and saw other people doing better than I was. Posting pics on FB of their fancy vacations…getting covered in the press…having more RSS readers or email subscribers or revenues…and I would start thinking, “Maybe they’re just better at this than I am.” Notice I didn’t say — they’ve practiced their skills more, or they’ve learned more strategies, or they’ve just been at it longer. No, I made it about them being a BETTER PERSON than I was.”

He continued working though, chipping away at the fears, and growing his business. It’s not something that happened overnight — he’s been working at this “blogging thing” for 8 years now.

The Knowing-Doing Gap

That’s the clinical or academic term for the space that exists between “knowing” what you’re supposed to do, and actually taking action on it.

For me this space is a gulf when it comes to acknowledging the fear of failure and doing something about it. I still listen to self-development nearly everyday, but find myself tuning things out if I’ve heard it before.

I say, “yes, yes, I’ve heard this before, let me find a new tactic.” But the value is in actively reflecting on the fears. This is work. It’s not something that happens when you half-ass it.

Reading and learning new case studies, though, and seeing how others approach their fear of small failure helps. It provides different lenses to see that fear, often so insidious, to spot it and face it down long enough to get back to the work we’ve set out to do.

#####

Photo Credit: epSos.de, Manuel Valadez Acuña