My two-year anniversary with Los Angeles approaches. Living here was an experiment, drawn out on cocktail napkins and e-mails before throwing my life into a car and arriving with no job, no apartment, and no clue. And as much as there is to love about LA, looking around at the trappings of my life, it’s obvious I never thought of it as more than an experiment.

And it’s like coming back home. It smells familiar. You can take off your shoes and get comfortable, because you’re in the hands of an artist, who may not show you where she’s taking you, but she won’t release you from her world either, until there’s nothing left to explore. I had forgotten – this is what made me want to tell stories in the first place.

That’s what (all non-affiliate links) A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan did. So did Everything is Illuminated (Jonathan Safran Foer,) The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (Junot Diaz,) City of Thieves (David Benioff,) and (crossing genres now) BRICK by Rian Johnson, 500 DAYS OF SUMMER by Scott Neustadter and Michael Weber and shit, okay really genres hopping Pain (Johnny Cash) and the time I listened to an artist whose first name was Neal and last name I left in Nashville at the Bluebird Cafe, who sang “That’s My Son” which still keeps me up at night, but right then I had to march up to him and thank him because that song meant the world to me, even though I knew I’d probably never hear it again and haven’t since.

Photos Credit: Arts Westchester

It’s strange to think our relationship grew from hate.

Well, maybe not as intense as “hate.” “Loathing” is close.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb notes in his book, BLACK SWAN, that we are creatures of revisionist history: we edit history as we see fit, giving cause or linking relationships between events that aren’t there. It’s part of human nature he says, to search for meaning in daily occurrences. If we don’t find it, we’ll make it up.

Which helped me realize this blog (in its half dozen itinerations, but especially in this current version) is an exercise of revisionist history as I work in the entertainment industry. I edit, filter, and draw causal relationships between events, hunting for logic that may or may not be there. And I do these things in the face of two truths:

One: I don’t know what I’m doing.

I base my decisions on my personal value system, my limited knowledge of the entertainment terrain, and the advice of my peers who are in similar positions. Yet at times I catch myself writing as if this was all part of the grand master plan I concocted while I was still in New York.

There is however, perverse comfort in the belief that most everyone in the entertainment field is groping blindly in the dark – some are just less aware of it than others.

The second truth is that in my effort to “make it” in entertainment, and to make it as a writer, I revise and filter my writing about making it in the entertainment and writing. Voices whisper each time I sit:

“Don’t write about how you view the executive/assistant relationship – what if you want an assistant job?”

“Don’t sound optimistic or hopeful about this prospect – you’ll sound naïve. Or worse, desperate.”

“Don’t call out certain rude tendencies of professionals in this industry – what if you offend someone?”

“Don’t talk too much about what or who you love – what if it changes? What if you have to take it back?”

These all boil down to fears I think a lot of us share: what if I’m held accountable for what I write? What if I have to make a stand? What if I upset the wrong people?

A solution is to write anonymously. Take my picture off this site, change the URL, and take cover behind the shroud of a pseudonym. But I think this is a cheat solution. As Travie McCoy of Gym Class Heroes so eloquently put it:

“Bitches post anonymous.”

A more acceptable solution starts by making a few admissions. I admit that most days:

- I don’t know what I’m doing.

- I am scared I’m doing the wrong things.

- I wish someone would reassure me, “you’re doing the right thing.”

I also admit that every day:

- I am accountable for my words. For what I say and write.

- I can do good work without knowing “what am I going to get out of this?”

- I should focus more on being honest and making a stand, and less on upsetting others.

Photo Credit: Stepzh

How many scripts does it take to turn a script reader sour to spec scripts?

I imagine not too long — if you’re patient and forgiving, somewhere in the low 200’s perhaps. Eventually you see the same mistakes repeated over and over again. Your patience wanes. Your forgiveness falters.

I embraced the process when I first started reading scripts — even as an unpaid reader.

I thought, if I pour myself into my reads, and take care to learn from the successes and mistakes (mostly mistakes) I’ll write better material.

It’s tough to keep up the positivity. Script after script, you offer the same notes: show don’t tell; what does your character want?; dialogue feels snappy but where is your story? And these notes are directed towards the good material… never mind the scripts sent by writers who obviously didn’t proof read: glaring typos on page one; lengthy sections of prose; scenes completely omitted explained with the words “insert scene here” to indicate something will eventually “fill in the blank.”

It gets more difficult to be kind. You can’t hold your tongue in your critiques. You lash out — cruelly, at times — if you think the piece warrants it: “Good, I hope their feelings are hurt. They’ll put more care into their work before sending it next time.”

Perhaps some of these mistakes are because of negligence. I think just as often they’re the mistakes of a first-time script writer. And a first-time writer needs to make his first crop of mistakes at some point in his career — you’re just the reader “watching” as he dips his toes. These are people who, if they put in their time and dedicate themselves, could probably create something quite good — it just wasn’t this project or this script. And what a terrible thing it would be to destroy someone’s potential.

Confidence to put material out to the world is difficult to build, but it’s easily crushed.

Which is precisely the temptation at times. To crush egos, to remind people, “you’re not as good as you think you are.” Each time I’m compelled to do so, however, I remember my first script. An assistant whom I interned for offered to read it and give me notes, and I took her up on it.

It’s only now I realize the gravity of the moment. This act was the catalyst that pushed me to show my work to others, to just put it out there. It taught me to stop treating projects like my darlings; that if you’re going to be a professional, you just do your best before casting them out to the world to see who thrives and who dies.

This assistant could have decided she was tired of reading bad scripts. She could have gotten onto her soap box and preached to me about all the beginner mistakes I made that she’s sick of seeing. She could have said, “Stop writing like this. We get it. You love the sound of your own voice.”

She didn’t. Instead she said, “It’s clear you’re a good writer. Here’s what you’re going to work on for your next script..”

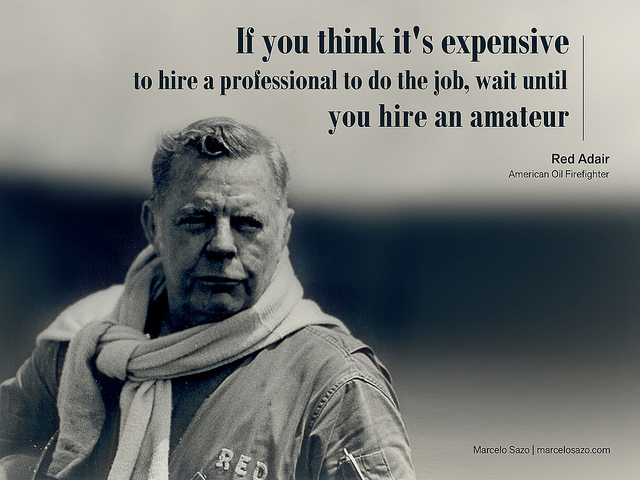

Photo Credit: Dmitry Kaminsky

“Don’t ask people if they would buy – ask them to buy. The response to the second is the only one that matters… Ask ten people if they would buy your product. Then tell those who said ‘yes’ that you have ten units in your car and ask them to buy. The initial positive responses, given by people who want to be liked and aim to please, become polite refusals as soon as real money is at stake.”-Tim Ferriss

With web content the details are different — we ask the audience to “buy” not with money but with time. However, the takeaway remains the same:

Don’t ask people “would you watch this?” Ask: “did you watch this?”

In my opinion, this is the most exciting element to creating and distributing a web series. This area is where you can give the biggest proverbial “f*ck you” to the big players out there. The ability to test and make adjustments based on testing is where independent producers can fully leverage their nimbleness, their flexibility, and willingness to innovate.

Testing is cheap.

Testing is simplified.

You don’t need focus groups. You don’t need tools to measure precise emotions.

The only thing you need is a system for your testing.

Below I’ve outlined a system for testing a web series. The system itself is untested, but they’re the steps I will take with the next project. I will update the post with tweaks and lessons learned as I proceed.

Step 1: Cut a Teaser

The key word is “cut,” not “shoot.”

Cutting a teaser means splicing existing content to recreate the tone or feel of your web series. Cost is virtually zero – basically only the opportunity cost of a bomb video editor who can execute. The purpose of creating the teaser is to test your concept – are people interested?

Most recently, this is how Brandon Bestenheider and Allen Bey created buzz and sold their spec script, GRIM NIGHT to Universal.

(This example is solely to give you an example of potential power of a teaser. The goal of our teaser is not to sell or create “buzz.” The goal is to test.)

To that end, the approach is not a “let’s put it on YouTube and see what happens!”

Definitely not. This is a passive approach, and it doesn’t generate the information you’re looking for.

The teaser allows us to ask very specific questions to gauge interest in the concept. We are asking questions to find out if it has viral potential, not hoping it will go viral.

Step 2: Test the Teaser

Show the teaser to a select audience. Ask them specific questions (there are both direct and indirect ways to ask these questions.)

“What do you think of this concept?” is not a specific question. Go deeper to get answers that will help you:

- “What part of this concept interests you?”

- “What parts bored you?”

- “What do you want to see more of?”

- “Where do you think this series is going?”

When you’re testing, you can literally sit there and gauge your audience’s reaction as they watch (note: practice with close friends, not strangers you approach at Starbucks and ask, “wanna see something?”)

What is their action immediately following the video?

- Do they ask for clarification?

- Do they repeat the viewing?

- Do they want to share with others?

Caveat: it’s unlikely you’ll disqualify your concept based on the teaser, unless reactions are particularly negative or you weren’t that attached to the concept anyway. That’s why specificity of questions is important – what can you learn from your audience

Step 3: Shoot the Pilot

Based off the teaser, your team moves forward and shoots the pilot. Most likely you’re bootstrapped and shooting on the cheap. (There are proactive ways, of course, to raise funding, i.e., Kickstarter, but I’d suggest taking this step after shooting the pilot.)

Employ guerilla tactics and get the pilot shot: steal locations, get people to work for free, etc. Get the project in the can.

The traditional model is cutting the pilot and shopping it around to producers, financiers, and distributors. Obtaining interest from any one of these parties is definitely a level of success. However, there are more steps to this model of testing if you want to remain independent.

Step 4: Test the Pilot

Cut 3 to 5 versions of the pilot.

Drive an audience to different landing pages featuring these cuts. When possible, ask audience members the same questions used in the teaser. Continue to gauge what elements of the pilot are confusing, and what elements resonate with the audience. The results of this testing will provide the necessary information to shoot the rest of your series.

These steps can be grouped under the catch all phrase, “creating buzz.” Except creating buzz is a vague concept, with no call-to-action or goals. Following the steps in this model, the goal is testing – and you generate buzz as a result.

Testing allows you to create a track record. A track record you can bring with you to, say, Kickstarter, and declare “this many people watched” (not, this demographic said they would watch, or we are trying to attract this audience.) Plus, you know what elements of the pilot they liked, what confused them, and how you’re going to use that information.

Now with that homework in your back pocket, how much more powerful are you when you ask for financing?

Step 5: Shoot the Series

The next step is the biggest risk: shoot the entire series, in the most cost effective manner possible. It’s a big step, especially without a buyer locked. This is your greatest investment yet, and you’re exposing yourself to large scale of failure.

But using this system for web content creation, look at what you’ve done in the previous four steps!

You’ve mitigated your risk by constantly testing, tweaking your approach based on feedback from an actual audience, and generated buzz for your project as a result. You’ve proven to potential investors that you can write, produce and package a product independently – that you value people’s time and money.

Who wouldn’t want to work with someone like that?*

*Note: I assume the answer is everyone, but this assumption remains untested. As I mentioned at the top, these are only my initial thoughts on the system. As I apply and test, I will update this post.

Photo Credit: Nick Gent

Over the last few months, a group of friends and I have been moving towards shooting a web series pilot. I’m learning a lot from the process, and I want to explore ideas surrounding the creative strategy of independent web content creation. Most of this is likely applicable to any independent project, but my focus is purely on web.

Project Sustainability

Independently produced web content must be looked at through a project sustainability lens as well as a typical production lens. This means more than shooting “guerilla style,” although guerilla production techniques play a role. This means in your development stage you must create some metrics of success and failure. I define success by two standards:

- Shipping. You finish. You put out a project and you distribute it, OR if you don’t finish, you’ve made the conscious decision to stop (because it’s not worth your time, because you’re not passionate about it, etc.)

- The project is SUSTAINABLE.

Sustainable = value of project > cost of project

As long as the VALUE is greater than COST, the project is sustainable. Simple, right?

Put another way: create VALUE and reduce COST.

What makes up a project’s value? The most obvious (yet smallest component in our example) is revenue generated. Other pieces include: satisfaction in creation, satisfaction in distribution (they are different,) potential revenue, potential exposure, potential leverage to a higher-profile project.

COST is made of two parts:

- Cost of the project = money cost + opportunity cost

- Money cost = how much cash do you front?

Opportunity cost = this is your time cost. What are you giving up to work on this project?

If VALUE > COST, it’s SUSTAINABLE, and you should continue moving forward. With an independent project where most of the value lies in the potential, the entire team must understand how this formula affects them.

Understanding the formula creates several takeaways.

High Project Value: what can you control?

In an independent production, current revenue is almost certainly zero. There are ways to increase current revenue which won’t be discussed here (using your relationships to find advertisers, sponsors, etc.) For now, let’s assume you can’t increase earned revenue. Then, what can you control?

What details can you get proactive about?

- Leverage and exposure –the proactive approach to leverage and exposure is becoming a contributing member of the web series sphere: connecting to content creators and marketers, understanding their projects, helping when you can, and being open about discussing your project. Note: this is in contrast to the passive approach which is posting it on your Facebook page and hoping it goes “viral.”

- Derive satisfaction from the project: be happy you’re working on it and you’re learning from it, without the expectation that fame and fortune will soon follow. It’s unlikely your project (or any project) will put you on the express rail to the top, but it might get you closer. Work with people you enjoy being around, have fun with it, and it won’t feel like work

Reduce Project Costs

If you’re involved in any kind of independent content production, you need to keep costs down. There are all sorts of interesting methods to do this. A discussion of all methods lies outside the scope of this post, but I want to point out one thing: I prefer to focus on one really big win to cut costs than bust my head trying to create a series of small wins.

Small wins are: craft services, extras, wardrobe, set dressing, etc.

In my opinion, the big win, where you’re going to save the most money is in concept. Concept happens in the development stage – YOU CAN MAKE / BREAK YOUR BUDGET BEFORE YOU START THE BUDGET. You’re committing your budget to a certain range at this stage, i.e., a high-tech thriller is more expensive than a slow-burn drama. Not to restrict anyone’s artistic vision, but when you independently finance you must physically create within your boundaries. Accounting for this during development, not after, is critical to ship.

- How cost effective is your web series?

- Does it require high production value to capture the audience’s attention?

- Or does it rely on something else?

That’s how Christopher Kubasic created his webseries, THE BOOTH IN THE BACK. “I was designing it from the outside in. I had certain rules that I wanted to work from. I wanted it to depend on actors rather than cinematic language, so that it would be less expensive than having to move a camera around to different locations or having to set up one shot after another.” (Read Blogcritic for the full article.)

Note that this doesn’t mean you can’t create a high concept web series. High concept is just an elevated way of telling your story or creating your vision, and it’s independent of money. I call this a HiCoLoCo (high concept, low cost) project.

You can spend hours and hours searching for inventive ways to cut on production costs when you’re in pre-production. Save a little here, a little there, skimp on this or that, for the sake of a project that’s intrinsically high concept high cost, i.e., explosions, fires, bullets, aliens, etc.

Or, front-load the process and invest significant time in creating something HiCoLoCo. Focus on the big win.

Reduce Opportunity Cost

Opportunity cost = what else could I be doing with my time?

Total opportunity cost is everyone’s collective time on the project. I think often we overlook opportunity cost completely, so even small steps can create dramatic savings:

- Everyone comes prepared

- Everyone comes on time

- Schedule meetings with clear objectives

- Have start and end times to meetings

The big win to save on opportunity cost, however, is about limiting the number of people you bring into the project. Instead of scaling the project to the maximum number of people, scale the right number of people to the project. In REWORK, Jason Fried notes we should:

“Embrace the idea of having less mass. Right now, you’re the smallest, the leanest, and the fastest you’ll ever be. From here on out, you’ll start accumulating mass. And the more massive an object, the more energy required to change its direction.”

In other words, grow slow. Bring in the right number of people you need, and go from there.

Conclusion

By no means is this an exhaustive discussion on sustainable models for web content creation. They are my thoughts and theories on the matter at this point and time, and as I apply the theory, I will add/edit the post with specific examples and takeaways.

Photo Credit: Mad Pal

Image the work we could do without memory.

If we worked without remembering all the times we failed:

- the product we announced would change the world.

- the novel we’d finally finish.

- the instrument we’d learn to play.

- the video that would go viral.

- the screenplay that’d give us our break.

- the blog we started and swore this time, we were going to post every day, no matter what…

…only to lose focus and steam, and offer an apology or an excuse before abandoning it?

Is it lack of desire or the memory of failure that keeps us from trying again? Not even failure specifically, but our feelings associated with failing (shame, embarrassment) that stops us from picking back up the pen, lacing up the sneakers, or grabbing the camera?

What terrifies me is people watching me put myself out there again and asking:

- Didn’t you already try that?

- Do you really think this time is going to be different?

- Why waste your time?

If we attacked our projects without memory of the shame, only the lessons we learned from our failure, how much affect could we have on our world?

Photo Credit: timbu

Being a professional is not your arrival to a level. Regardless of the field, you don’t stake a claim to professionalism, or petition for permanent residency. Getting paid doesn’t make you a professional. Neither do sponsorships, or praise from your constituents — all whom may consider themselves professionals based the above standard.

Professionalism happens minute-to-minute. You are only as professional as your last decision.

I remember a recent moment where I lost sight of that, and I made the unprofessional decision.

After being deceived and rather unceremoniously forced to close down on a production, the producer asked if I could come in on strike day and assist with closing down the set.

I had every excuse to not go in: that we had been deceived about our finances, our contracts were reneged, I was let go and it was no longer my job to close down the office, and there was nothing left for me to gain.

I had every excuse. So I took them all.

I told him sorry, I was unable to come help close.

The second I got off the phone, I knew: being in the right doesn’t make it right.

The professional decision was to close, regardless of how things fell out. The professional decision was to finish the job.

See, I made this poor choice because I let the voices of others weasel themselves into my ear. These reasonable and experienced voices belonged to people who had been involved in many more productions and gotten burned dozens of times before. They were looking out for my best interests when they told me: don’t work for free, don’t get walked over, don’t let anyone take advantage of you.

Well-meaning voices all, but they’re strangely silent now as I sit here alone, hoping weeks or months from now I’ll look back and realized I did the right thing, and knowing that I won’t

Photo Credit: Stefan Leijon

Timeliness has become such a rarity that arriving on time is the new gold standard.

We’re bombarded with people who don’t value their time or the time of others. So much so that just showing up for work, being physically present at the agreed upon time is a Gold Star worthy endeavor. Being on time is appreciated, but you’re supposed to come on time. It’s nothing to brag about. It’s expected.

With competition everywhere, and all the scalable, inexpensive and fast tools at our disposal to communicate, create, and affect our world, how long can hold ourselves to this low standard of physical presence?

What can we accomplish when we begin to expect more from ourselves and our peers than just “being on time?” What can we build when our expectation isn’t just to come, but to come:

Mentally present — having considered (on your own time) the issues at hand. As prepared to propose solutions as you are prepared to raise issues.

Emotionally invested — having thoughts about the direction of the project, knowing full well you might look stupid voicing them and putting them out there anyway.

Willing to take risks — not prepared to accept a scenario because “that’s the way it is.” Challenging assumptions (e.g., it costs too much, you can’t do that, it’s too hard.) Pushing each other into discomfort zones because that’s where great things happen.

If that’s how we showed up, how much more could we accomplish?

Versus the (general) current approach: everyone arrives 15 minute late. Gab and BS for another 15 minutes. Finally, a rallying cry is heard, “let’s get started!” before everyone scrambles to remember why you were meeting in the first place.

There’s more to showing up than showing up.

Photo Credit: veri_ivanova